While my last post defined consent…

Revocable words or actions freely performed by a person who is capable and aware that create agreement with another party to permit some specific act.

It didn’t really tell us much about how we interact with consent in our daily lives.

Nor did it discuss how we are ‘consented’…

Part 3: How do we DO consent?

Philosophical Models: Two philosophical consent models are evident in the literature.

Autonomous authorisation model: This model emphasises the importance of a clear and affirmative choice by those who provide consent (Schermer et al, 2014). The consentee must make a clear and dispositive choice (final and determinative) to consent before the consenter can undertake the identified action. The focus for this model is on the clearly articulated choice of the consentee to consent.

Fair transaction model: The consenter is morally permitted to undertake an action requiring consent from the consentee. However, in order to be a fair transaction the consenter must have treated the consentee fairly and respond reasonably to the consentee’s token or expression of consent - or what the consenter reasonably believes is the consentee’s token or expression of consent. In this model the consenter can undertake the identified action if they have a reasonable belief that the consentee is or has already consented (Schermer et al, 2014). The focus for this model is on the reasonable belief of the consentor that consent exists.

Both philosophical models represent outcomes in the consent process. However, valid consent requires more than just an expression of the consentee’s decision and detection of that decision by the consentor. This means that, as shown in our consent philosophy model in the diagram below, these models address half of the necessary overarching requirements for each actor in the consent transaction. They do not address reasonable understanding and articulated information, the presence of which would complete the overall consent philosophy framework:

1. The Consentor articulates information necessary to secure informed consent.

2. The articulated information assists the Consentee to form a reasonable understanding of what is being consented and why.

3. The reasonable understanding is necessary for decision-making to convey an articulated choice regarding whether or not to give consent.

4. The strength, intonation and spoken words of the articulated choice when weighed against the originally articulated information should aid the Consentor in forming a reasonable belief regarding whether consent exists to proceed.

We were unable to locate philosophical models from the literature to support the input pieces of the consent philosophy model. For this reason we consider the philosophical picture for consent remains incomplete.

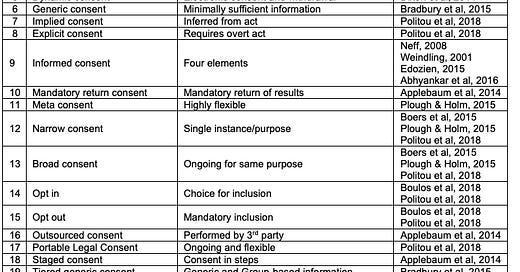

Practical models: The practical models of consent explain the approach a consentor, your doctor or this website, might use to seek consent from you. Bear in mind that the practical model only explains the underlying approach to consent, and that each practical model can be applied in a myriad of different Application Models - such as cookie consent or medical treatment consent that we will discuss in the next post. We identified twenty-one practical models were evident in the literature. The distinguishing characteristics for each type of practical model are identified in this table:

Bona-fide consent: Where the consentee makes an informed choice after dialogue with the consentor, in a collaborative relationship. The focus is on allowing the consentee to be an active party in the decision-making process and ensuring they understand the options and risks involved before making their decision (Edozien, 2015).

Collaborative consent: Where the consentor and consentee engage in a bimodal dialogue that allows the consentee to ask questions and discuss the consent decision prior to making that decision (Edozien, 2015).

Contrived consent: The model of consent commonly applied in medical practice whereby the consentor (doctor) ostensibly presents the consentee (patient) with a menu of choices (with either a large quantity or very little information) and an immediate response is elicited. The focus is not on the consentee’s understanding of the information, but rather on their signalling assent for the consentor to proceed with treatment (Edozien, 2015).

Digital aging consent: An approach that attaches an expiration date to the consent. When the date is reached the consent expires and is no longer available (Politou et al, 2018).

Dynamic consent: On reviewing information regarding potential activities or uses, the consentee can provide or revoke consent electronically at any time using a web-based platform (Dixon et al, 2014). This approach is considered to be closer to informed consent than contrived consent (Dixon et al, 2014).

Generic consent: A model wherein consentees receive minimally sufficient information with which to make what consentors ostensibly describe as an informed decision (Bradbury et al, 2015).

Implied or Explicit consent: While implied consent may be inferred from some act of the consentee such as their providing a piece information that is necessary to proceed, explicit consent requires an unequivocally direct and affirmative action such as answering a specific question in written or oral form or clicking a button that says something like ‘I Agree’ (Politou et al, 2018).

Informed consent: Initial criteria for informed consent in in the medical domain to allow permissible medical experiments is said to have arisen out of judicial obiter at the closing of the 1947 Nuremberg medical trials (Neff, 2008; Weindling, 2001). These criteria included that consent must be voluntary, which the judges described in terms of: (i) legal capacity1; (ii) freedom of choice; (iii) absence of force, fraud, deceit, duress, overreaching or ulterior constraint or coercion; with (iv) provision of sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the subject matter involved as to make an understanding and enlightened decision2.

The UK Supreme Court in 2014 clarified the sufficient knowledge component of the legal doctrine of informed consent as a requirement for full disclosure of material risks to the consentee. Such information should be tailored to the individual consentee, with consideration as to whether a reasonable person in that particular individual’s position would likely attach importance to the risk, or whether the consentor is or should reasonably be aware that a particular individual would attach importance to it (Edozien, 2015). The informed decision is one based on accurate information about all options and their consequences, people’s evaluation of these options in accordance with their own values, and a choice made based on trade-offs between those evaluations (Abhyankar et al, 2016).

Mandatory return consent: Consentees are told that if they consent to the initial process (for example, a genetic test) that they are consenting to the automatic mandatory return of certain types of actionable outcomes or findings (Applebaum et al, 2014).

Meta consent: Combines the broad and dynamic consent models with additional options for blanket consent and blanket refusal (Plough & Holm, 2015). Meta consent is both prospective and retrospective and allows individuals to choose how they wish to provide consent for future research such as secondary use of data collected in the past or that will be created and stored in the future (Plough & Holm, 2015). Consentees are informed about the types of research that may wish to use their data, and they can decide what types of research may request access to their data in future and their preferred method for receiving requests. They can also provide blanket consent for particular types of research or research groups, or give blanket refusal for others.

Narrow and Broad consent: While narrow consent is limited to the specific use context, broad consent includes agreement for future or ongoing use of a similar nature, under the same governance framework, and is standard practice for example in many biobanks, genetic registries and big data projects where specific future uses cannot be imagined at the time of consenting the individual (Boers et al, 2015; Plough & Holm, 2015; Politou et al, 2018). In this way narrow consent focuses on the single instance - disclosure of information about the specific research that will be conducted in this instance, while broad consent is more concerned with the overarching research context - the general type of research and overall governance process (Boers et al, 2015).

Opt In or Opt Out: Opt in occurs when the individual actively provides consent, while an opt out consent process automatically includes all target individuals who must explicitly signal their denial of consent in order to be withdrawn (Boulos et al, 2018; Politou et al, 2018). Opt out consent processes are often used by governments to increase the number of organ donors lists by including all people with drivers licenses unless they actively signal their opposition.

Outsourced consent: Where the consent process is performed by a qualified third party outside the consenter’s organisation (Applebaum et al, 2014).

Portable Legal Consent: A consent model proposed by Consent to Research3. In this model the consentee makes an ostensibly informed decision to enrol their health data in research by uploading consent and the data they consented to sharing onto the Consent to Research website. Participants can return to the website and withdraw consent at any time, and while it is described as ‘rigorous’ and ‘honesty focused’ (Politou et al, 2018), the project appears to have failed and ceased operations at some time between 2018 and 2020.

Staged consent: Similar to tiered-binned generic consent (see below), consent for the initial process (for example, a genetic test) is sought at the beginning. Consent regarding whether or not the consentee wishes to be made aware of incidental findings (for example, potential other genetic conditions) or those unrelated to the original purpose, is delayed until after the initial process has completed and findings are known. Staged consent allows the focus to be on the initial process or reason for consent, and defers other matters requiring consent until such time as they arise (Applebaum et al, 2014).

Tiered generic consent: Similar to generic consent except that the consenter first identifies broad concepts and common denominator elements required for all consentees. Tier 1 information is that which is indispensable and which should be presented to all consentees. Tier 2 information provides additional details that are relevant to particular populations that the consentee belongs to and is only given as needed (Bradbury et al, 2015).

Tiered-binned generic consent: An extension of tiered generic consent where information on potential issues or outcomes are linked together (binned) and when even only one item in that bin is observed as potentially relevant for this individual consentee, details of the entire bin are provided as part of the informed consent process. Information on potential outcomes from other bins where no items within those bins have been observed and that are therefore not relevant to the consentee are not provided (Bradbury et al, 2015). This model is intended to reduce the possibility of the consentee becoming overwhelmed by too much information provided in a too comprehensive manner. Consentees are often also advised that more comprehensive information may be provided on request at a later time (Bradbury et al, 2015).

Traditional, Comprehensive or Specific consent: Where the consentee receives comprehensive information prior to consent. This approach is used in genetic testing wherein the individual receives comprehensive information about the conditions being scanned for, potential incidental findings and the meaning of different results (Applebaum et al, 2014; Bradbury et al, 2015).

Framework of consent

Now that we have identified the philosophical and practical models of consent, we can try to understand how they work together to provide a framework for consent approaches we see every day.

Authors of consent literature present a wide range of theoretical (Schermer et al, 2014) and practical models (Edozien, 2015; Politou et al, 2018) and applications (Habib et al, 2022; Bruyndonckx et al, 2020) for consent. While some are described or applied within only a single domain (Bradbury et al, 2015), others are presented as generic (Politou et al, 2018; Schermer et al, 2014), being adaptable across a broader range of situations and circumstances.

I propose a framework for consent built of three layers of models as illustrated in the following diagram:

In the upper layer, philosophical models describe an overarching theory for consent operation as a normative ethical proposition. They advise assumptions regarding appropriateness and operation of the practical consent model as well as any resulting legal frameworks and legislation (Schermer et al, 2014). The philosophical model informs and is engaged within the practical model such that it may be possible that selection of a particular philosophical model with its inherent ethical or legal position may reduce the pool of available practical models available to the consentor4. One or more philosophical models may act to guide either the input (what informs consent decision-making?) or outcome (what conveys the consent decision?). It may only be when the practical model is implemented that the effect of incorporating the philosophical model can be identified.

In the middle layer, practical models are distinguished by how the necessary elements of consent are applied in the decision-making process of consent. Practical models may be differentiated by the amount of information provided to the consentee at the time of consent (e.g.: Staged and Tiered Generic Consent); type of activity consent is tied to (e.g.: Implicit or Explicit); duration of consent once given (e.g.: Digital Aging Consent); or whether consent is deemed to already exist or not, often by operation of some rule or law (e.g.: Opt In or Opt Out).

In the lower layer, application models describe how individuals interact with the consent process and communicate a specific type of consent decision. The application layer is generally tied to a particular consent need or outcome (e.g.: surgical consent, data collection consent) that is often evident from the user interface (UI), consent form, or direct interaction that occurs between the consentor and consentee. The application model is the outward or consentee-facing manifestation of the process for consent required by the selected practical model and prescribed by the consentor, an ethics board or enacted in legislation.

In turn, the framework for consent models visually represents how the philosophical model informs selection of the practical model, and the application model is the outward expression of the practical model that interacts with the consentee and captures their consent decision.

In the next post we will investigate applications (or application models) for consent.

Join me then when we ask… How do I consent?

References

Abhyankar, P., Velikova, G., Summers, B., & Bekker, H. L. (2016). Identifying components in consent information needed to support informed decision making about trial participation: an interview study with women managing cancer. Social Science & Medicine, 161, 83-91.

Appelbaum, P. S., Parens, E., Waldman, C. R., Klitzman, R., Fyer, A., Martinez, J., ... & Chung, W. K. (2014). Models of consent to return of incidental findings in genomic research. Hastings Center Report, 44(4), 22-32.

Boers, S. N., van Delden, J. J., & Bredenoord, A. L. (2015). Broad consent is consent for governance. The American Journal of Bioethics, 15(9), 53-55.

Bradbury, A. R., Patrick-Miller, L., Long, J., Powers, J., Stopfer, J., Forman, A., ... & Domchek, S. M. (2015). Development of a tiered and binned genetic counseling model for informed consent in the era of multiplex testing for cancer susceptibility. Genetics in Medicine, 17(6), 485-492.

Bruyndonckx, B., Santantonio, O., & Hellemans, P. (2020). Connected vehicles and GDPR- A status update after the public consultation. Lexology. Last accessed: 21 August, 2022. Sourced from: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=f5ee720f-a5f6-4b6d-8de1-5b41ba0f5288

Dixon, W. G., Spencer, K., Williams, H., Sanders, C., Lund, D., Whitley, E. A., & Kaye, J. (2014). A dynamic model of patient consent to sharing of medical record data. bmj, 348.

Edozien, L. C. (2015). UK law on consent finally embraces the prudent patient standard. Bmj, 350.

Habib, H., Li, M., Young, E., & Cranor, L. (2022, April). “Okay, whatever”: An Evaluation of Cookie Consent Interfaces. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-27).

Neff, M. J. (2008). Informed consent: what is it? Who can give it? How do we improve it?. Respiratory care, 53(10), 1337-1341.

Ploug, T., & Holm, S. (2015). Meta consent: a flexible and autonomous way of obtaining informed consent for secondary research. Bmj, 350.

Politou, E., Alepis, E., & Patsakis, C. (2018). Forgetting personal data and revoking consent under the GDPR: Challenges and proposed solutions. Journal of cybersecurity, 4(1), tyy001.

Schermer, B. W., Custers, B., & Van der Hof, S. (2014). The crisis of consent: How stronger legal protection may lead to weaker consent in data protection. Ethics and Information Technology, 16(2), 171-182.

Weindling, P. (2001). The origins of informed consent: The international scientific commission on medical war crimes, and the Nuremberg Code. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 37-71.

The elements of legal capacity include that the person must be of sufficient age and mental competency to understand what they are agreeing to and the impact it will or could have for them. There are no singular minimums for these elements which may change according to the circumstances of the current situation and the reason consent is being sought.

https://media.tghn.org/medialibrary/2011/04/BMJ_No_7070_Volume_313_The_Nuremberg_Code.pdf

http://weconsent.us

For example, a philosophical model based on the requirement for a clearly articulated choice from the consentee would preclude use of an Opt Out practical model.