As I said in the previous post… it’s only once we’ve defined and understand what IS consent, that we can start to identify what IS NOT consent…

Part 2: What is consent?

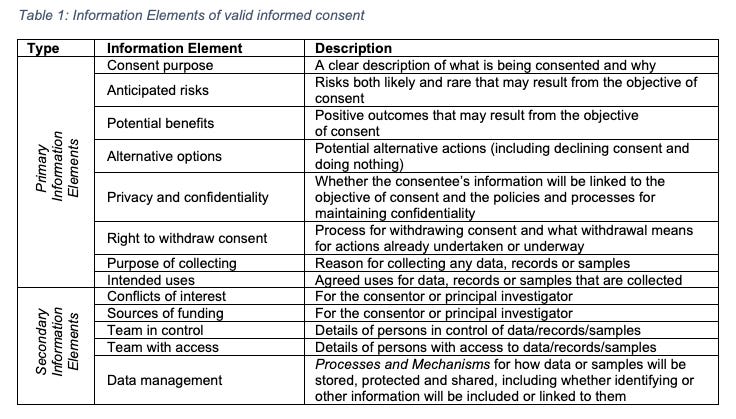

Philosophers, ethicists and researchers generally speak of consent in terms of some collection of elements necessary for achieving valid or informed consent. Many also discuss disclosure of a range of information that supports the consent decision-making process - including most of the primary information elements listed in Table 1, along with any secondary information elements that the consentor feels are necessary given the consentee’s particular circumstances. Characterisations of informed consent in the academic literature incorporate as few elements as information and consent (Beauchamp, 2010), through to a broad range of as many as four or five that contemplate the presence of coercion and whether the person was heavily medicated or in pain and therefore incompetent when making the decision to consent.

Faden and Beauchamp (1986) together prescribe five elements: disclosure, comprehension or understanding, voluntariness, competence or decision-making capacity, and authorisation. Neff (2008) describes an informed consent form developed as part of her research to meet regulatory and medical research council requirements that provides a range of information (details about the medical study, risks and benefits, alternatives, compensation, description of procedures and contact details for the researchers). That information, along with confidentiality, voluntariness and the ability to withdraw (revocation of consent) were the author’s four necessary elements for informed consent. Neff goes on to discuss capacity issues (freedom from pressure, competence to consent and issues of surrogate consent) but does not include these factors in her table of elements of consent. Beauchamp (2010) alone proposed five elements (competence, disclosure, understanding, voluntariness and consent), and describes a basis around those elements in which the individual gives informed consent only if one is competent to act, receives thorough disclosure, comprehends that disclosure, chooses voluntarily, and finally, consents. However, after some discussion he eventually concludes that only three of those elements (understanding, voluntariness and consent) are central elements (Beauchamp, 2010). Finally, when contemplating his definition for consent, Birckhead (2011) describes consent as premised on voluntariness and defined from elements he couches in four questions that imply consent only exists when: (i) the act is not done in exchange for something of value like money; (ii) the parties are on equal footing, such as being peers; (iii) the consentee is competent (both developmentally and intellectually); and (iv) when the act is not being done in order to survive. When considering the question of autonomy, Birckhead highlights the inconsistency of seemingly arbitrary boundaries that allow someone we might consider incompetent to consent in one situation - for example: where a minor wants to marry, get a tattoo, have an abortion, or purchase property, as competent to consent to other things - for example: the same minor between the ages of 13 and 16 can consent to participate in full-contact sports like football, karate and boxing, sexual intercourse with a peer, and some medical procedures1.

Much of the literature on consent generally proceeds in the manner of those described in the paragraph above - in that authors identified and described a particular subset of elements necessary to their description of valid or informed consent. The elements described by each author were not always the same, and in following their citations we found they regularly missed or failed to attach significance to other elements that were described in the works they cited as the basis for their own definition of consent.

Our definition for consent

Working with a small group of researchers who are clinicians, nurses, health informaticians and health law experts I sought a complete definition for consent.

In language as plain as the subject allows, we defined consent as:

Revocable words or actions freely performed by a person who is capable and aware that create agreement with another party to permit some specific act.

Our consent definition is consistent with the broader aggregation of much of the consent literature, including Arstein-Kerslake & Flynn (2016), Borghi et al. (2013), Faden and Beauchamp (1986), Neff (2008), Whitley & Kanellopoulou (2010), and Woods et al. (2019). However, we were unable to locate a definition in the literature that, like the one we provide above, presented with or could be interpreted as containing all eight of the necessary elements described in Table 2.

The eight necessary elements of consent

The eight necessary elements we propose for genuine valid consent were separately identified from across a broad range of legal, ethical, philosophical and medical literature. This section defines and describes the purpose of each.

Revocability: Revocability is the ability to withdraw, or cancel, consent that has already been given. The laws in many jurisdictions establish a right for withdrawal, or revocation, of consent2. Revocability is an aspect mentioned by many authors when discussing elements of valid and informed consent (Tomkovicz, 2020). For some, revocability is a central keyword in the title that the reader is then unable to find mentioned even once in the body of the published research article (Pohls, 2008). For others, revocability is a basic core concept of informed consent that, once mentioned, is never defined or described such that the reader is left to question its supposed importance (Richards & Hartzog, 2019). The Collins dictionary tells us that something with revocability is able to be cancelled3. The normative notion is that valid and genuine consent should not be permanent - that once given, and at any time thereafter, the consentee should be able to withdraw their consent and choose no longer to proceed (Harvey, 2008; Tomkovicz, 2020). An example might be where someone who, after having consented to some medical intervention, withdraws that consent prior to receiving treatment. A lack of revocability is central to why some believe consent through notice4 or implied license consent is invalid (Tomkovicz, 2020). However, the act of withdrawing consent does not in most circumstances mean that acts or events already undertaken on the basis of that consent can be undone5 (Santos et al, 2019). In some cases complete withdrawal is impractical or impossible6 and the act of revocation simply serves as withdrawal from ongoing or future participation (Santos et al, 2019). There are also situations where, as one author puts it, it does not matter how valid and genuine the consent is; the only real moral point is that such consent can never be withdrawn, once given7 (Fulda, 2013). As such, this element arises as scale from fully revocable to irrevocable such that its characterisation in different consent applications varies.

Intentionality: An act has intentionality when we undertake it in accordance with the plan and purpose that was previously agreed (Nelson et al, 2011). Intentionality requires knowledge of why we are engaging in agreed actions that are planned to result in disclosed specific outcomes (Larson, 2012, Reyes, 2020). Intentionality incorporates both the outward appearance - purposeful words or actions that indicate agreement and demonstrate an ongoing willingness to proceed, and inward consciousness - awareness of the meaning of what was agreed and why (Larson, 2012; Reyes, 2020).

Autonomy: Consent validity ultimately depends upon the consentee’s state of mind (Wefing & Miles, 1973). To possess the quality of autonomy a consent decision must be made absent any form of coercion, and consent given voluntarily8 (Nelson et al, 2011). Autonomy is an individual’s capacity to self-govern (Stoljar, 2011) which becomes diminished where they are deliberately kept ignorant or are deceived by the consentor (Taylor, 2004). While choice and voluntariness are central to consent, voluntariness remains the most neglected element - especially in medical practice and research (Applebaum et al, 2009; Beauchamp, 2010). In criminal law, impaired voluntariness may appear where a party other than the accused surrenders the accused’s rights, for example by consenting to a search of the accused’s property (Wefing & Miles, 1973). Impaired voluntariness in medical research can result from poor safeguarding of groups identified as vulnerable to coercion or undue influence9. Factors that impair voluntariness also include situations: where researchers offer monetary or other compensation for participation; when participants are recruited by their own clinician or in a facility where they are already receiving healthcare as they may be hesitant to decline, believing that to do so might antagonise the caregiver or compromise their ongoing access to care; where there is an existing power imbalance that means the consentee believes they are subordinate to the consentor; where the participants are involuntarily committed patients or prisoners; when addicts are enrolled in studies that either involve administration of the source of their addiction or are paid money that can be used to purchase it; and patients who are unable to access or afford medical treatment for a condition who are encouraged to participate in return for that treatment (Applebaum et al, 2009). The last two groups may also be defined by the additional element of desperation that acts to amplify the nonvoluntary nature of their consent (Swift, 2011).

Capacity: A necessary component for valid consent is ensuring that the consentee is competent and able to give consent. There are two types of capacity that must both be present: intellectual and developmental. Intellectual capacity is an amalgam of four requirements: understanding seeks whether the consentee is able to comprehend the new information and demonstrate they remember, recall and can recite it; appreciation seeks to ensure the consentee is able to relate the information provided in an appropriate way to their own situation; reasoning ensures the consentee is able to compare and contrast their options in a logical and rational manner; and communicating the choice necessitates they are capable of making and clearly communicating their consent decision (Kim et al, 2011; Moye et al, 2007). Understanding is also affected by the extent of injury, pain, and whether the person has consumed alcohol, analgesic or anaesthetic medications that cause sedation and affect alertness (Neff, 2008). Developmental capacity, sometimes also called legal capacity, can consider both the consentee’s age10 and maturity11 (McLean, 2000; Wadlington, 1973).

There have long been established circumstances in domains such as medicine where the requirement to ensure capacity may be set aside: (1) the ‘emergency exception’ where lifesaving treatment is needed but the person is incompetent, incapacitated or otherwise unable to give consent; and (2) certain situations where consent is arbitrarily withheld, often due to a religious conviction of the parent or caregiver (Wadlington, 1973). In the first situation the medical practitioner may proceed to providing necessary care to save a life, based on a belief in implied consent - in which we imply (or infer) that the person would naturally want us to undertake measures to save their life. In the second situation practitioners, through hospital administrators, will often seek appointment of a surrogate guardian for the specific purpose of consenting necessary medical care (Wadlington, 1973).

Certainty: We are usually consenting an individual because the act they will be giving consent to carries some potential for personal harm. A moral duty exists that requires the consentor to ensure the consentee is fully aware of what they are agreeing to, including any potential benefits, risks and alternatives, prior to making the decision to consent. While it is possible for the consentor to be uncertain regarding the probabilities for both risk and the potential outcome, they must honestly and openly provide information about the purpose of consent and any alternatives, including any advantages and disadvantages of each (Calman, 2002; Taylor, 2004). These disclosures ensure both that the consentee is fully informed when making their decision (autonomy), and allow them to form the specific intention regarding any decision they make (certainty) (Taylor, 2004). In some instances, especially those where the decision may be to withhold consent, certainty regarding the outcome may be necessary knowledge and the most important element for justifying the decision (Meadow et al, 2002).

Understanding: Provision of adequate and relevant information enhances basic understanding when making decisions (Reyes, 2020). Poor understanding is common, even in people with intact decision-making abilities (Dunn & Jeste, 2001). Many different problems can cause inadequate understanding, such as poorly prepared or presented consent information, or a consentee with a limited education level (Dunn & Jeste, 2001). There are approaches associated with ensuring a greater degree of understanding. These approaches include providing the consentee with an ability to discuss details with and ask questions of a suitably qualified and informed person (Neff, 2008), and incorporating the use of information visualisations like that shown in Figure 1 to aid the consentee to comprehend probability information that could directly inform their decision-making process (Fenton & Neil, 2010; Fuller, Dudley & Blacktop, 2002). Care must be taken while improving or enhancing understanding as it is possible for the consentee to be manipulated or ‘nudged’ against their own interests (Richards & Hartzog, 2018).

Purpose: The informed consent process can be derailed by a failure to provide full and frank disclosure (Fatema et al, 2017; Macklin, 1999). Information provided should be consistent with the purpose - that is, the specific permission being sought (Fatema et al, 2017). The purpose for the informed consent process has been described as a permission spectrum ranging from routine paperwork and a courtesy gesture (this is what I am going to do, okay?), obtaining simple permission (can I do this?), informed permission (this is what I will do, why I will do it, these are the potential risks and benefits of doing it, these are the alternatives, are you ready for me to proceed?), shared decision-making (shall we discuss this?), to enabling and empowering the consentee to make decisions for themselves (What do you want to do?) (Hammami et al, 2014). Historically, the overarching purpose for informed consent has been to simply obtain informed permission without necessarily promoting any ability for the consentee to participate in the decision-making process (Hammami et al, 2014). We now seek to respect the consenting individual by promoting autonomy and understanding, and participation in the decision-making process (Hammami et al, 2014; Jefford & Moore, 2008).

Specificity: There are two areas where specificity is necessary in the consent process - both the information provided to support the decision-making process and the action being consented should be directly relevant and particular to the purpose for which consent is being sought. It has been argued that any focus on perfect specificity would do little more than exponentially increase consentor effort because consentees could potentially request unending degrees of detail (O’Neill, 2007). However, increasing the clarity and specificity of consent information can improve consentee comprehension, increase relevance and improve consentee response without necessarily changing the amount of material being disclosed (Haut & Muehleman, 1986; Lambrecht & tucker, 2013; Perni et al, 2019).

Together, the eight necessary elements of consent can be brought together to help us understand models of consent.

In the next post we will explore the many different models of consent that have been proposed, and how those models can be brought together into a framework…

Join me then as we ask… How do we DO consent ?

References:

Appelbaum, P. S., Lidz, C. W., & Klitzman, R. (2009). Voluntariness of consent to research: a conceptual model. Hastings Center Report, 39(1), 30-39.

Arstein-Kerslake, A., & Flynn, E. (2016). Legislating consent: creating an empowering definition of consent to sex that is inclusive of people with cognitive disabilities. Social & Legal Studies, 25(2), 225-248.

Beauchamp, T. L. (2010). Autonomy and consent. In Miller, F., & Wertheimer, A. (Eds). The ethics of consent: Theory and practice, Oxford University Press, USA. pp 55-78.

Birckhead, T. R. (2010). The youngest profession: Consent, autonomy, and prostituted children. Wash. UL Rev., 88, 1055.

Calman, K. C. (2002). Communication of risk: choice, consent, and trust. The Lancet, 360(9327), 166-168.

Dunn, L. B., & Jeste, D. V. (2001). Enhancing informed consent for research and treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, 24(6), 595-607.

Fatema, K., Hadziselimovic, E., Pandit, H. J., Debruyne, C., Lewis, D., & O'Sullivan, D. (2017). Compliance through Informed Consent: Semantic Based Consent Permission and Data Management Model. PrivOn@ ISWC, 1951, 1-16.

Fenton, N., & Neil, M. (2010). Comparing risks of alternative medical diagnosis using Bayesian arguments. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 43(4), 485-495.

Fulda, J. S. (2013). The limits of consent. Sexuality & Culture, 17(4), 659-665.

Fuller, R., Dudley, N., & Blacktop, J. (2002). How informed is consent? Understanding of pictorial and verbal probability information by medical inpatients. Postgraduate medical journal, 78(923), 543-544.

Hammami, M. M., Al-Gaai, E. A., Al-Jawarneh, Y., Amer, H., Hammami, M. B., Eissa, A., & Qadire, M. A. (2014). Patients’ perceived purpose of clinical informed consent: Mill’s individual autonomy model is preferred. BMC medical ethics, 15(1), 1-12.

Harvey, M. (2008). Towards a public human tissue trust. Case W. Res. L. Rev., 59, 1171.

Haut, M. W., & Muehleman, T. (1986). Informed consent: The effects of clarity and specificity on disclosure in a clinical interview. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 23(1), 93.

Jefford, M., & Moore, R. (2008). Improvement of informed consent and the quality of consent documents. The lancet oncology, 9(5), 485-493.

Lambrecht, A., & Tucker, C. (2013). When does retargeting work? Information specificity in online advertising. Journal of Marketing research, 50(5), 561-576.

Macklin, R. (1999). Understanding informed consent. Acta oncologica, 38(1), 83-87.

McLean, K. (2000). Children and competence to consent: Gillick guiding medical treatment in New Zealand. Victoria U. Wellington L. Rev., 31, 551.

Meadow, W., Frain, L., Ren, Y., Lee, G., Soneji, S., & Lantos, J. (2002). Serial assessment of mortality in the neonatal intensive care unit by algorithm and intuition: certainty, uncertainty, and informed consent. Pediatrics, 109(5), 878-886.

Kim, S. Y., Appelbaum, P. S., Kim, H. M., Wall, I. F., Bourgeois, J. A., Frankel, B., ... & Karlawish, J. H. (2011). Variability of judgments of capacity: experience of capacity evaluators in a study of research consent capacity. Psychosomatics, 52(4), 346-353.

Moye, J., Karel, M. J., Edelstein, B., Hicken, B., Armesto, J. C., & Gurrera, R. J. (2007). Assessment of capacity to consent to treatment: Challenges, the “ACCT” approach, directions. Clinical Gerontologist, 31(3), 37-66.

Neff, M. J. (2008). Informed consent: what is it? Who can give it? How do we improve it?. Respiratory care, 53(10), 1337-1341.

Nelson, R. M., Beauchamp, T., Miller, V. A., Reynolds, W., Ittenbach, R. F., & Luce, M. F. (2011). The concept of voluntary consent. The American Journal of Bioethics, 11(8), 6-16.

O’Neill, O. (2017). Some limits of informed consent. In The Elderly (pp. 103-106). Routledge.

Perni, S., Rooney, M. K., Horowitz, D. P., Golden, D. W., McCall, A. R., Einstein, A. J., & Jagsi, R. (2019). Assessment of use, specificity, and readability of written clinical informed consent forms for patients with cancer undergoing radiotherapy. JAMA oncology, 5(8), e190260-e190260.

Pöhls, H. C. (2008, October). Verifiable and revocable expression of consent to processing of aggregated personal data. In International Conference on Information and Communications Security (pp. 279-293). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Richards, N., & Hartzog, W. (2019). The pathologies of digital consent. Wash. UL Rev., 96, 1461.

Santos, C., Bielova, N., & Matte, C. (2019). Are cookie banners indeed compliant with the law? deciphering eu legal requirements on consent and technical means to verify compliance of cookie banners. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.07144.

Taylor, J. S. (2004). Autonomy and informed consent: a much misunderstood relationship. Journal of Value Inquiry, 38(3), 383.

Tomkovicz, M. (2020). If You're Reading This, It's Too Late: The Unconstitutionality of Notice Effectuating Implied Consent. Emory LJ, 70, 153.

Wadlington, W. (1973). Minors and health care: The age of consent. Osgoode Hall LJ, 11, 115.

Wefing, J. B., & Miles Jr, J. G. (1973). Consent searches and the fourth amendment: Voluntariness and third party problems. Seton Hall L. Rev., 5, 211.

Whitley, E. A., & Kanellopoulou, N. (2010). Privacy and informed consent in online interactions: Evidence from expert focus groups.

Concluded with self-determination (autonomy) and through application of the clinician’s assessment of the minor’s Gillick Competence.

Including Art.7(3) of the EU GDPR which states that it should ‘be as easy to withdraw as it is to consent’, and Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) at Sect 36(2)(m).

https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/revocable

A simple example of circumstances where consent is implied by virtue of the consentor’s having posted a notice include when a building has a sign near the entrance stating that by entering the building you agree to being searched on exit, or their use of CCTV to record your image, or their use of facial recognition for identification and fraud prevention.

The position that withdrawal of consent should not devalue already conducted research, decisions or work already undertaken on the basis of that consent is supported, for example, by Art 7(3) of the EU GDPR which provides that ‘the withdrawal of consent shall not affect the lawfulness of processing based on consent before its withdrawal’.

For example, if the consentee through their doctor allowed their health data to be available to researchers and two years later seeks to withdraw that consent after their data has been anonymised and merged with a large aggregate collection of other anonymised records - or after the researchers have already published some findings that were based on data which included the consentee’s own record, such withdrawal if allowed and required by law could potentially force retraction of published findings and necessitate complete redevelopment of the aggregate anonymised dataset in order to ensure the person who withdrew consent’s anonymised data was no longer present.

The examples given in Fulda (2013) include: autoassassinophilia - where a person becomes sexually aroused by fantasizing about their own death at the hands of a particular person - a fantasy which they may eventually seek made reality; and Muslim suicide bombers who seek a death that they are told has political or religious meaning here, and will result in fulfillment of their hope and belief in unending good sex in the afterlife. We would also suggest that in many jurisdictions consent to surrender a child for adoption, at the very least once the child has been removed and placed in the care of their new guardians, may also be an irrevocable consent. Similarly, a contract, once consented and thus formed and after the other party has acted to their detriment in fulfillment of their obligations may represent a situation where consent to the contract can no longer be withdrawn. An exception to this would be where the contract has a withdrawal clause - which in retail situations may also incorporate a penalty clause (such as a fee for restocking or cancellation)

Even consenting an act of necessity such as urgent surgical intervention to save life or preserve function can still possess the element of voluntariness.

Examples identified from the literature include: children, prisoners, pregnant women, mentally disabled persons, and those who are financially or educationally disadvantaged.

Age as a factor of the capacity to consent does not present as a single consistent factor. For some activities like consenting to most contracts, genital piercings, tattoos or to a police interview, the age of majority is the minimum requirement to consent in many jurisdictions - which is 18 in some, 21 in others. Most countries have a minimum age requirement for consenting to online data collection and processing - 13 in the UK, and 16 under the EU GDPR. The age of consent for sexual intercourse varies from country to country, and where one party is under the age of majority, depending on the age of the older party or the difference in age between both parties.

American jurists speak of the mature minor doctrine which arose out of the decision in Smith v Seibly 72 Wn. 2d 16 (1967) and allows healthcare workers to treat a minor under the age of 18 years based on assessment and documentation of the youth’s maturity and hence ability to choose or decline treatment. In the United Kingdom and other jurisdictions that follow the English common law tradition (including Australia and New Zealand) Gillick Competence is the standard established from Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority anor [1986] AC 112 wherein the court decided that in limited circumstances a health practitioner could assess the maturity of the minor, specifically whether the child possesses ‘sufficient understanding and intelligence to understand fully what is proposed’ (at 187[D]).