Dido Harding's almost £40bn Boondoggle

Track and Trace, A Failed Disgrace, Three Times the UK Government Lost Face

Summary:

Baroness Harding was appointed in a manner the High Court has since declared as unlawful.

Baroness Harding has a poor recent history in similarly senior leadership positions.

Billions were awarded in un-tendered and uncontested contracts, with large amounts going to firms that may present with worrying conflicts-of-interest for the Baroness.

In June 2020 our research group correctly predicted many of the ways in which the then-proposed track and trace app would go on to fail. As with all our papers that challenged the government Covid narrative, no journal would publish it.

The NHSx track and trace app was unequivocably an abject failure and embarassment for Baroness Harding and the UK Government.

The replacement Apple/Google API-based app developed by a private contractor presented with many similar issues to the NHSx app, and failed to live up to expectations.

The entire test, track and trace infrastructure (including the apps) was expensive and ineffective, the impracticality of which had been demonstrated by us before the money was even budgeted.

When we factor in costs for the current financial year that are currently unreported by Commons, the estimated total expendature overseen by Baroness Harding falls between £35-37bn, but that doesn’t account for close-out costs for the hundreds of contracts still running, nor for decommissioning the entire test, track and trace infrastructure - all of which will edge it closer to £40bn

In May 2020 and only around 8 weeks after the Coronavirus fiasco started in the UK, Baroness Dido Harding, Tory MP John Penrose’s wife, was quietly tapped on the shoulder and through an exercise of what some call ‘chumocracy’, was handed control of key elements of the UK’s Covid-19 response. Her appointment, which the High Court in 2022 declared unlawful, would see her chair two aspects that we will discuss here: (i) mass testing; and (ii) track and trace.

If nothing else, Harding had a chequered past - having been pushed to resign from her CEO post at TalkTalk after presiding over the telecommunication’s provider as they lost £60m and were fined £400,000 for what was described as a security failing resulting in one of the largest data breaches in history, and going on to be a Director of The Jockey Club whose Cheltenham Race Course was inexplicably allowed to stay open and run large racing fixtures in March 2020, causing an allegedly large number of entirely avoidable Covid-19 cases, even as the rest of the country was already being prepared to go into lockdown.

The Covid Contracts Scandal

Referred to in Hansard as dodgy crony contracts that wasted taxpayers’ money by the Billion, Harding’s contracts to Randox were the earliest signal we had that her appointment was going to be expensive for us, and a windfall for her friends. The conflicts of interest started with Matt Hancock as Member for Newmarket gifting the job to Harding, a director on the Board of Stewards of Newmarket’s The Jockey Club. The conflicts of interest continued when she, in her role as chair of the Covid-19 response, gifted the mass testing contract to the Grand National’s keystone advertiser, Randox - who, thanks to a Channel 4 Dispatches investigation, the public would later find out were nothing less than grossly negligent in their handling of what became a multi-billion Pound testing contract.

From their first contract in 2020 through until early 2022, Randox, both on their own account and on behalf of their strategic partner Qnostics Ltd, were awarded more than 22 testing contracts, 60% of which were awarded under emergency procurement rules without tender or competition. In March 2022 the total value of the Randox contracts was more than £776m, and when we factor in the costs of testing across the NHS labs, the total cost to the UK taxpayer for Covid-19 testing sits at around £2bn today.

Some would rightly question whether the entire £2bn Covid-19 testing spend represents value for money. Especially when the antigen tests were found by a Cochrane review to only be 73% accurate. And while the Government told us that PCR tests never produce more than 5% false positives or 5% false negatives, and some doctors claimed a false positive was rare, others demonstrated false negative rates of up to 30% and false positive rates of between 3 - 6.8%, and described the terrible impact of false diagnosis on patients. These rates are compounded by the errant use of excessively high cycle threshold (Ct) settings and misdiagnosis of a three-gene test based on observation of two, or even only a single gene. In some weeks more than 65% of positive result notifications, or ‘cases’, were questionable because they failed to meet even the original manufacturer-defined standards. All of this leaves aside the high rates of contamination (e.g.: here, here and here), and repeated failure to report which virus (Sars-CoV-2, Influenza A or B or RSV) had triggered the positive result in what almost always were multi-virus PCR test kits.

This video helps to explain just how bad the false positive ‘cases’ issue is even with the supposedly accurate Covid-19 PCR tests.

The Track and Trace App Fiasco

On the 27th of May 2020 Matt Hancock called a press conference to announce the new Test and Trace program and in doing so, called on the public to “stay at home” when told. The following day the UK government went ‘live’ with their initial, manual, test and trace system. Testing was extended from front line healthcare workers, travellers and those going into hospital to include everyone with any of the burgeoning list of alleged coronavirus symptoms. Anyone testing positive would be called by one of what we were told was 25,000 call handlers, and asked to share a list of all others they had been within 2 metres of for more than 15 minutes during the preceeding two days. In turn, those people would be called and told to self-isolate for 14 days, and to keep any children in their household out of school. At the same time the first version of the Track and Trace App was to be trialled on the Isle of Wight.

During May I and others were interviewed and quoted in the mainstream media regarding what we believed was the government’s misplaced faith in the upcoming contact tracing smartphone apps. By early June a group from within our ranks had released this paper describing contact tracing apps generally, and why they would fail. From that paper I provide the following abridgement:

Issue 1: Context and Application

Contact tracing has traditionally only been successfuly used for diseases with low prevalence: meaning diseases where there is only a small number of cases in the community at any given time1; and low contagiousness: meaning diseases that are not easily transmitted between individuals. Examples of diseases where contact tracing has been applied include: tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, Ebola and sexually transmitted diseases, and on review, many of these examples report uncertain or indeterminate efficacy for contact tracing2. With a rapidly increasing global population, international airline travel, megacities and mass transit, such traditional contact tracing alone is unlikely to contain even a minimally contagious disease3.

At the time we were sceptical that any standalone contact tracing approach, manual or automated through the use of a smartphone app, could contain a high-prevalence highly contagious disease like COVID-19.

Our scepticism was borne out in reality. The various contact tracing infrastructures using call centres and contact-alerting apps that were developed by different governments played little or no role in the effective containment of disease. This can be evidenced in that if we accept that ‘case’ numbers legitimately continued to rise after the apps were released, then we must also acknowledge that the track and trace infrastructures could not have been effective. The UK was not alone in abject failure in this regard. Australia have also shuttered their $21m track and trace app. After two years the Australian Government’s app had identified hundreds of thousands of false positives and only two true positive unique cases.

Issue 2: Privacy and Confidentiality

Governments, the mainstream media and even Apple touted the Apple/Google API as the privacy preserving contact tracing tool. Some journalists disingenuously reported that privacy, security and human rights scholars supported the Apple/Google approach. They linked to a contact tracing joint statement signed by a long list of academics that, whilst generally supporting any effort towards a technological solution for track and trace, actually only says it applauds the Apple/Google effort because it will simplify and speed up the wider ability to develop such apps. They caution against the collection of private information from users from use of the tech giant’s platforms, and the calls by some for Google and Apple to open up their infrastructures and enable even broader data collection.

While the mainstream media made it seem like Google and Apple were making the software, it was actually private contractors engaged by each government that produced the the actual contact tracing apps. In each case a State authority had developers produce a locally coded and customised contact tracing App for citizens to download that simply used the Apple/Google API in what developers call the backend.

Once again our scepticism was borne out in reality. In spite of vendor privacy and security claims, numerous breaches were identified involving both the State-customised Apps and the underlying Apple/Google API. These included that: (a) while users were expressly told in press releases that log files containing personal information would not be stored locally on their device, log files were not only found, they were accessible in plain text to other installed Apps4; (b) what was supposed to be securely encrypted App data was identifiable to State intelligence and law enforcement and capable of being copied while it was in-transit on the internet between the user’s smartphones and the State’s Track and Trace servers5; and, (c) State authorities were profiting through the sale of App data such as the user’s location linked to the device’s Google Advertising ID6.

All of this leaves aside that: (i) users were required to create an account and provide personal details when setting up the track and trace app; (ii) that the user's IMEI (smartphone serial) number and cellphone subscriber (telephone) number were attached to every packet leaving the app, and every packet of data passing through the cellphone provider network; and (iii) that the data was received by and maintained on a central health authority server and accessible to an unknown number of staff from undisclosed authorities that we now know included the health authority, police and the third-party software developers.

Issue 3: Overall Ineffectiveness

We modelled the number of people an infected person may come into contact with using the calculations employed in the design of the UK Government's NHSX-specific app7, and employed the following assumptions in a best-case scenario (that you can read more about in our paper) that was intended to give the contact tracing app (CTA) the best chance of being successful:

The assumptions used in our calculations include:

a) The infection clock starts from exposure;

b) From day 5 the infected begins to shed the virus;

c) Patients may become symptomatic between days 5.5 and 11.5;

d) At day 12 every infected is considered to by symptomatic;

e) Each infected comes into close contact with 36 people in a 14-day period, pro rata for the period between day 5 and when they become symptomatic;

f) Every infected has self-isolated from when they became symptomatic, or as soon as the app told them to (whichever came first);

For the 6 o’clock path shown in the target diagram below, we present the absolute best-case scenario where 100% of the population have smartphones, install the CTA, are tested, immediately self-report and immediately self-isolate. This scenario, whilst being quite impossible, would actually contain the disease in only two cycles, or 14 days.

For the Australian (9 o’clock) and UK (3 o’clock) scenarios we begin from the position that 40% (Australia) and 60% (UK) of the population respectively have installed the app and immediately self-report and/or self-isolate when alerted. These percentages were provided by the Health Authority of each country as being the required adoption level within the population for the CTA to be a successful containment tool.

As these scenarios played out, we calculated under our absolute best-case wherein people who were alerted by the app or who had symptoms at day 5 all immediately self-isolate. The issue with this is that we know some people’s symptoms will not be severe enough at first for them to believe they have the disease and seek medical advice. This is human nature.

Furthermore, smartphone ownership for adults in Australia and the UK was at the time less than 80%, reducing to 40% in the key COVID-19 demographic, the over-65s. To get 60% CTA penetration in the overall UK population, more than three quarters (76%) of all smartphone owners would have had to install, register and use the app. This assumes absolutely no loss to follow-up, which occurs where a user either cannot use the app due to compatibility issues, stops or forgets to use the app, or removes the app from their device for any reason. For comparison, average loss to follow-up in a clinical trial is 6%.

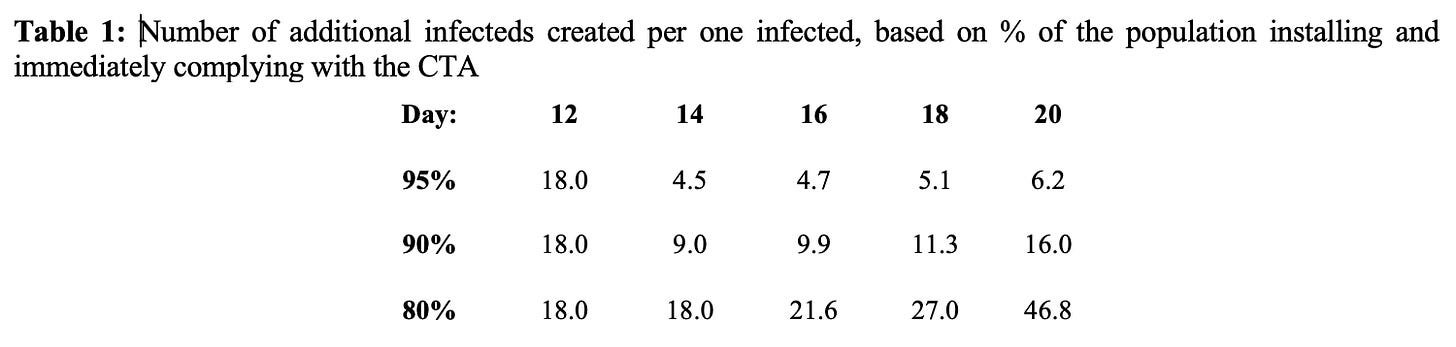

Given that it was clear that neither the Australian (40% CTA use) or UK (60% CTA use) scenario could ever be successful, a final set of calculations was performed seeking the sweet spot: that number below 100% for CTA adoption in the overall population where the number of secondary cases was manageable by manual contact tracing and other containment methods, and the health sector generally. The following table presents the results of those calculations and we find the sweet spot for CTA uptake in order to control COVID-19 had lay somewhere between 90 and 95% of all citizens. As discussed, such high uptake fot the CTA was simply not credible nor even possible.

As such, our scepticism in the possible efficacy of CTA was also borne out in reality.

Total Spend

Baroness Harding’s total spend during her time as chair of the Covid-19 response, and specifically on the test, track and trace includes:

£500m on 2000 private sector consultants

£720m for call centre contact tracing staff

£63,000 annual take-home salary for herself for a 2-3 day working week

£30,000 additional concurrent annual salary as chair of the NHS Improvements board

And while we were told she would not receive a salary for taking charge of Hancock’s PHE replacement, the DHSC-led National Institute for Health Protection (NIHP), DHSC responses to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests actually seem to suggest she is receiving (an undisclosed) salary for that role

£10.4bn on testing during the first year (2020-2021) that included: £4.2bn on mass testing, £3.1bn on NHS laboratories and associated costs, £10.8m for the original failed NHSX track and trace app and at least £25m for the first failed version of the private company developed Apple/Google API based app.

£1.8bn that NHST&T described as being spent on ‘contain activities’

£0.9bn on what the expendature report describes as ‘tracing activities’

£15.7bn for all test, track and trace activities for the second year (2021-2022)

In total the estimated disclosed expendature on test, track and trace for the June 2020 - February 2022 period was close to £30.1bn. Many of the test, track and trace functions have continued since February 2022 (hospitals still provide RAT tests to those staff and patients who want them, laboratory services and equipment purchased during 2020-2021 are under license and support contracts that carry annual contract payments, the servers and software for the track and trace app are still running even though that program is now being shuttered, and many DHSC and test, track and trace staff are still employed and receiving public sector salaries). Therefore we must factor in the current financial year.

Given that the track and trace app and associated infrastructure was only referred to be taken down last month, we must consider the costs of it’s continued operation and vendor support between March 2022 and February 2023 for which we do not currently have a Commons budget report. When we factor in an estimated budget of between one third (33%) and half (50%) of that spent for 2020-2021 and 2021-2022, the missing year (2022-2023) would come in at between £4bn and £7bn - for a total estimated spend of £35-£37bn. And that does not account for any unknown or undeclared expendature during all three financial years. Nor does it account for any close-out costs for the hundreds of open contracts nor decommissioning costs - all of which could bring the total spend closer to £40bn.

Conclusion

While it is often decried as impolite to point and say I told you so, it does seem warranted in this case. We were likely not the only research group to go on to point out the various issues and correctly predict CTAs failure, but our own literature review at the time showed that we were, at least, one of the first to do so with solid math and reason.

When we consider the total amount of money spent on these completely ineffective test, track and trace projects during Dido Harding’s Covid Task Force chairmanship, and couple that with the half-billion pounds spent on unused Nightingale Hospitals and all the other ineffective Covid projects, every single citizen of the United Kingdom - all 66million men, women and children - could have been given a shiny new expensive iphone. Or a short holiday. Or had a significant chunk of their now extortionate electricity bills wiped out.

Anything would have been better than what we got.

Armbruster, B., & Brandeau, M. (2007). Contact tracing to control infectious disease: When enough is enough. Health Care Management Science, 10, pp 341-355.

Hussain, S. F., Watura, R., Cashman, B., Campbell, I. A., & Evans, M. R. (1992). Audit of a tuberculosis contact tracing clinic. British Medical Journal, 304(6836), 1213-1215; and Mwongela, S. W. (2018). A Mobile based Tuberculosis contact tracing and screening system (Doctoral dissertation, Strathmore University); and Kiss, I. Z., Green, D. M., & Kao, R. R. (2008). The effect of network mixing patterns on epidemic dynamics and the efficacy of disease contact tracing. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 5(24), 791-799.

Niehus, R., De Salazar, P. M., Taylor, A. R., & Lipsitch, M. (2020). Using observational data to quantify bias of traveller-derived COVID-19 prevalence estimates in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, 3099(20), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30229-2

https://themarkup.org/privacy/2021/04/27/google-promised-its-contact-tracing-app-was-completely-private-but-it-wasnt

https://www.fastcompany.com/90508044/north-dakotas-covid-19-app-has-been-sending-data-to-foursquare-and-google - note that the Care19 app from North Dakota is still available on both the Android and Apple App stores, and on each identifies that it uses the Exposure Notification API (aka the Apple/Google API) - https://apps.apple.com/us/app/care19-alert/id1513945072

Merrick, R. (2020). Coronavirus: NHS contact tracing app needs 60% take-up to be successful, expert warns. The Independant. Last accessed: 04th May, 2020. Sourced from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/coronavirus-app-uk-nhs-contact-tracing-phone-smartphone-a9484551.html

Thanks for the thorough analysis. The Australian government app was completely useless and a shameful waste of money. (It required people to leave Bluetooth on (flattening their battery) and needed to be running on top of apps. - apart from all the other fundamental problems). Embarrassingly bad.

Thanks for this eye-opening expose. I think the pre-test probability of this working was zero anyway - no large scale government IT attempt has ever been successful. The post office saga where the computer glitches resulted in the unwarranted imprisonment of postmasters should be at the front of everyone in the UK's mind whenever the government proposes anything like this..