This is the first of two articles I will be writing about my experiences of the last two weeks.

While it isn’t in the common vernacular and doesn’t easily convey meaning in the same way as annus horribilis (Latin for the ‘horrible year’ or, as some colourfully and colloquially describe it, the year of hell), horribilis duas hebdomades (Latin for ‘horrible two weeks’) is certainly an accurate descriptor for what I have just experienced. Even if I know it isn’t over yet.

Medical Trials

Before I embark on my tales of woe, I want to discuss something else. It seems that many researchers and clinical people tend to be reticent to participate in the human-participant medical research they may encourage their patients to enrol in. That is, at least, unless the doctor himself has an orphan (rare) disease for which a unicorn medicine can fetch more than USD$219,000 per dose, or where the doctor has a rapidly fatal condition like glioblastoma for which their claimed cure can draw significant headlines, attention and funding to the university research centre. Headlines and stories like the ones below portrayed Dr Richard Scolyer’s glioblastoma ‘cure’ as nothing short of miraculous; making survival of 12 months seem almost impossible without it and suggesting he was brain tumour free because of it.

I have written about the poor quality framing of statistics in Scolyer’s articles before, so I will summarise by saying that: (i) the sad truth is that the glioblastoma median survival rate is 14.6 months (meaning some die before this and some live well beyond it - up to 25 years in fact!); (ii) at least 25% of adults (1-in-4) are surviving beyond diagnosis for a year; and (iii) as a result of his already receiving care beyond that of many non-medically trained and less financially able people, Scolyer was already somewhere between 25-40% likely to survive beyond 12 months even without his ‘miracle cure’. Sadly, and as with most people pretty much everyone diagnosed with glioblastoma, Dr Scolyer’s cancer returned. His unicorn doesn’t appear to be anything alike a ‘cure’, but I applaud him on two fronts. First, he developed and tested a new immunotherapy process for cancer treatment. It might not work yet, but it creates a new frontier for others to step into that may lead somewhere in the future. Second, and this is the most important thing, he tested that frontier treatment not on some poor unsuspecting patient who was on the verge of dying anyway. He tested it on himself. He was, to be unceremoniously blunt, his own guinea pig.

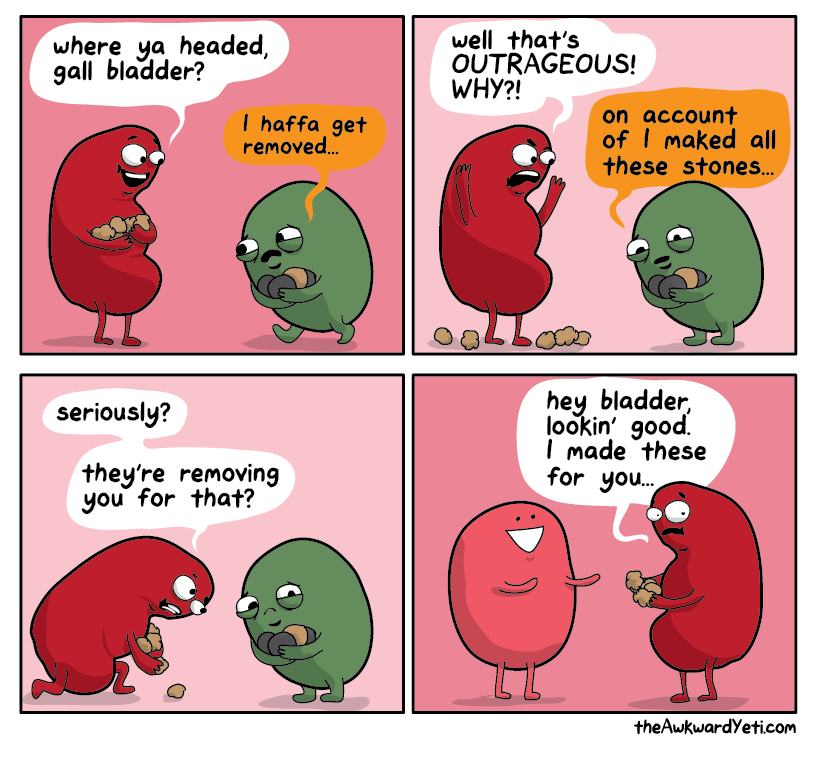

When I had my first two bouts with what appeared to be cholelithiasis (gallstones), as someone who already spends an inordinate amount of time on medical research I began to research the problem. Very quickly I came across a collection of literature spanning more than five decades discussing use of a compound called Ursodeoxycholic Acid (UDCA) to dissolve gallstones and reduce what is often termed as gallbladder sludge (more on these things later). One of the first papers I read was a UK-based work, the Hall study, that had surveyed gastro-biliary surgeons, finding that only 42% had previously used UDCA and more than half were unaware of either its existence or the academic and medical literature on its potential with gallbladder disease. That work also reviewed eight prior UDCA studies, finding seven of those works (88%) provided favourable results regarding the use of UDCA for patients with biliary pain. Seeing that there were significantly more relevant trials that could be included in such a review, I decided to conduct my own. But, and more importantly, I decided that like Dr Scolyer I was going to be guinea pig in my own single-patient clinical trial. I would take UDCA for whatever appeared to be a reasonable duration based on my review of the clinical trials and see what the outcome was. For me.

Ursodeoxycholic Acid (UDCA)

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), also known as ursodiol, is a naturally occurring bile acid found in small amounts in human bile and in larger quantities in bear bile. It is used as a medication to treat various liver and gallbladder conditions. It was first employed in traditional Chinese medicine over 100 years ago by herbalists and physicians alike. Before discovering its effectiveness in dissolving gallstones, its primary use was as a liver tonic. Today, extensive evidence suggests that UDCA is beneficial in various types of liver pathology. However, most of the data still points to its therapeutic effect in treating gallstone disease. Cholelithiasis (gallstones) are a common and exceedingly costly digestive disorder if considering the number of hospital admissions and cholecystectomies performed annually. It is a complex disorder where genetic and environmental factors contribute to the susceptibility to the disease. The primary non-invasive treatment for cholesterol gallstones is oral litholysis with bile acids like UDCA. UDCA has been shown to decrease the biliary cholesterol saturation markedly and has found use as an alternative to cholecystectomy in patients with gallstone disease.

While there is considerable history showing UDCAs effectiveness at treating these conditions with little to no appreciable side effect profile, since at least 2007 and especially into the 2010s there has been considerable publication pressure from gastrobiliary surgeons to consider UDCA entirely ineffective and to immediately operate to remove the gallbladder. This may be similar to the pressure we see on other medications, everything from antimalarials, anthelmintics (drugs that kill parasites or worms) to opioids, to deprecate even well-established safe and effective cheap and out-of-patent medications in favour of either a new in-patent and expensive tablet, or a profitable surgical intervention.

My Review

I sought literature that described a human trial of UDCA for patients with gallstones that provided information on: (i) patient demographics and primary diagnosis (biliary colic, gallstones, functional dyspepsia or cholecystitis); (ii) clinical outcome measures (changes in bile acids, gallstone size, bile cholesterol etc); (iii) side effects; (iv) dosage; and (v) overall outcome (from no change to complete dissolution of gallstones as observed on ultrasound). My search identified 29 studies of which 22 provided sufficient detail for inclusion in my dataset. The 22 included studies along with the Hall study that started me off are listed in the following PDF.

Results (The Cliffs Notes)

Don’t worry, I am going to try and keep this pretty simple.

The 22 included studies included 1,958 patient participants (range: 2 - 527) and were characterizable in the following groups: placebo (12), placebo plus single dose (9), placebo plus multi-dose (3), single dose (17) and multi-dose dose size effect (5) studies. A dose size effect study gave participants two or more different size daily doses to see which was more effective. In a majority of studies (9) patients were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or a single static daily dose (e.g. Okus et al, 2021; Venneman et al, 2008; Tuncer et al, 2003). In some studies (4) patients were randomly assigned a particular dose (e.g. Erlinger et al, 1984). In another (1), the dose was adjusted or titrated at a fixed point during the study (Bateson et al, 1980). While studies generally sought to identify whether there was a beneficial effect from taking UDCA, studies that utilised multiple dose sizes also sought the daily dose that was most effective in a range of dose sizes from 125mg to 1,000mg (e.g. Tint et al, 1982; Erlinger et al, 1984).

Women were over-represented in many of the included patient groups (e.g. in M:F ratios, 29:97 in Gleeson et al, 1990; 49:128 in Venneman et al, 2006; and 0:25 in Okus et al, 2021). This may be explained by other studies that describe gallstone incidence being as much as two or even three times higher in women. Whether the study is one of a novel surgical treatment, medication or vaccine, it should be a universally established requirement that authors transparently provide all the necessary sub-group details to enable readers to understand the treatment effect and outcome between the sexes and different age groups. This disclosure can aid readers to identify where incongruous statistical phenomena may have occurred; such as Simpson’s Paradox (where a trend appears in several groups individually but disappears or reverses when groups are combined) and Berkson’s Paradox (where we see a counterintuitive result often found in statistical tests of proportions where the data is biased or censored). Each link in the previous sentence will take you to a very simple explanation video of the statistical phenomena by mathematics Professor Norman Fenton. However, across the reviewed papers this sub-group analysis was not always consistently or clearly provided.

Overall, and without trying to bore you with data and statistics, the key interim findings I made were that: (i) the optimum dose appeared to be 750mg taken as 500mg in the morning and 250mg in the evening, with meal; (ii) the median duration was 18 months; (iii) very few side effects were reported of which none could truly be characterised as serious (the worst was described as severe diarrhoea that resulted in sufficient fluid loss for 3 out of the 1,958 patients (0.15%) to necessitate withdrawal from the trial); and (iv) patients could be easily approximated into one of three outcome groups in a ratio of roughly 30:40:30.

Outcome Groups

At the top end, around 30% of participants are reported as having complete or substantial dissolution of their gallstones without incidence of even mild cholecystitis or biliary colic. Members of this group received UDCA therapy for at least eighteen months and sometimes in excess of two years. While it is possible, or even probable, that there will be some return of cholelithiasis in future, the impact of UCDA was significantly beneficial for this group.

In the middle, around 40% of participants appear to have had some moderate to significant dissolution of their gallstones sometimes with an occasional mild bout of cholecystitis or biliary colic. The median duration of intervention for this group was 18 months. Return of cholelithiasis (rebound) was more frequently observed in this group. It is possible on the evidence observed that continual UDCA treatment could effectively avoid cholelithiasis. Whilesome studies weakly suggest that extended term consumption of UDCA may have effects on other aspects of our health, such as bone density, there have been studies including patients who were on UDCA for over 12 years without side effects.

In the bottom group, the remaining approximately 30% were described as failing to realise any beneficial effect from UDCA. However, this conclusion was confounded by the fact that many of the participants had some early (within the first weeks to months of the trial) event of mild to severe cholecystitis or biliary colic during or after which they were immediately given a cholecystectomy (gall bladder removal). This effectively removed them from the UDCA clinical trial before the intervention had had sufficient time to take effect or record meaningful data.

My Outcome

In my own little one-person study I took UDCA for a total of 18 months, with the last dose almost exactly twelve months hence. At the end of that period an ultrasound showed I had no cholelithiasis or thickening of the gallbladder wall, suggesting the treatment had been effective for me. However, given the last two weeks of hell (my horribilis duas hebdomades) and my near-week in hospital it is clear the effect was transitory. That I rebounded, or worse, possibly that it only works while I am taking it. It may be that I needed to take it for upwards of 5 years as the 4-12 year study suggests and that as such, I simply stopped too soon. As I sit writing this, I am acutely aware that, like around 15% of some populations now, my time with a gallbladder is rapidly coming to an end. I am not pleased. Either way.

In my next article I am going to discuss a deplorable act of abuse I witnessed and reported while in-patient, and how it may be possible that the cultural and professional changes in overall nursing demographic and care in some, or many, NHS hospitals may actually be enabling increased incidence of patient abuse against infirm and often elderly white British patients.

Erratum:

Thanks to reader Felicity Sisley for correcting my barely competent Latin! As she righly points out the three adjectives must agree with the noun, which itself is feminine, nominative plural. I always hated Latin. Reminds me of that great Monty Python sketch…

Poor you Scott! Persistent pain and feeling unwell is horrid. Let’s hope a very quick op, and an uncomplicated almost outpatient stay for surgery will see you on the road to recovery.

I think you’re right about the changes in ‘healthcare’, that are leading us to a place where abuse and disrespect towards some patients and not others is being normalised. The incidents I’ve experienced myself, or others have told me about, is really concerning. A culture of disrespect, lack of care, compassion and competent care is emerging and I suspect there’s another, yet to be revealed agenda at play. I initially thought it was personal or maybe to push patients to seek self funded options, based on ‘the NHS doesn’t have the resources to waste on patients like you’ comments, followed by ‘I can do so much more for you in my private practice’ etc. Then I tried to offer words of comfort to an elderly lady who had waited two weeks to see a GP, because she genuinely felt and looked ill, who then sent her packing without assessment, with ‘you’re getting old, what do you expect me to do about it’ as he showed her out, annoyed by her presence wasting his time. Another distressed, just retired acquaintance, was told to ‘sort her menopause out because it was affecting her husband’s mental health’. It took two years to diagnose his rapidly advancing dementia for which there was little to no support, let alone any compassion about the devastation it caused at a time, putting feet up on a world cruise after retirement should have been on the agenda.

On a better note, my own horrible week, has looked like this….After trying to get to at least talk to a GP about my son’s rapid onset, monster sore throat, (classic strep), fever and ‘very poorliness’, I also waited up all night for a call back, that never came until 8.30 the next morning, despite me making a nuisance of myself. Eventually the pharmacist down the road, assessed him, prescribed/dispensed antibiotics and had us out the door within less than 15 minutes! Next, an out of hours emergency dental service, several miles away, saved the day and treated me very well after about 50 calls trying to get a NHS appointment locally. The local hospital (12 minutes away) emergency service wouldn’t see me because I was out of their catchment area…..Sadly there was absolute mind numbing despair along the way because I was in serious pain. My dentist of many years dumped her NHS patients when a well known private group took over, as did others at the same time. This has created a major deficit between service demand and available provision, yet again! I’m now sick, in pain, on antibiotics reflecting on what was really on offer to us, when in need of fairly basic care, had I been able to cough up the cost of a private GP consultation, £50 on line, I’m told, or significantly more to see and get treated by a private dentist. I have to wonder if there’s something in the air or water making us sick, because the phone and internet failed at the same time! In my paranoia, I wonder if I was cancelled in an hour or 48 of greatest need!

Sorry for your horrible experience, often if there is a rebound effect from medication it can be worse than the initial problem. Good for you reporting the abuse you witnessed in hospital I am not surprised it happened as I think it has been happening under the surface for a long time, abuse of any kind can be subtle and hard for people to recognise but you are right conditions in the NHS is lending itself to abusive practices and I think it is becoming more overt.