LL Part 6: The Incredible Dr Dewi Evans

The self eggrandising, controversial, and opinion-laden professional expert witness

Following on from our previous post (here)

A former paediatrician sometimes called ‘Doctor Evidence For Hire’ is the prosecution’s linchpin ‘expert witness’. Retired since 2009, evidence shows that rather than as Dr Dewi Evans led under oath regarding the National Crime Agency contacting him to assist on the case - Dr Evans had insinuated himself into the case early on by contacting the police first and offering his services. He testified that he thought he ‘could help’, ‘give advice’, ‘review case notes’ and ‘form an opinion of what led to the collapses of Child A and Child B’. Evans became involved in the Letby case when he travelled from Wales to Cheshire to ‘visit’ Cheshire police because, he said, there were concerns regarding the number of deaths at CoCH which were ‘unusual’ and which exceeded expectations. Defence counsel and no doubt many others saw this as ‘touting for business’. This assertion is supported in that during his ‘retirement’ he established a company called Dewi Evans Paediatric Consulting Limited that is listed on LinkedIn and Expert Witness selling his services as an expert witness for hire. His company reports current accounts with cash at hand of over £108,000 for the financial year ending 2022, and on review of the last several years accounts appears to have invoiced totals between £80,000-150,000 annually during the period of the Lucy Letby investigation.

While admitting he has very limited neonatal knowledge and was never a neonatologist, he testified that in spite of his being retired from hospital work for a decade-and-a-half he believed his skills were still current and that, in any event, neonatal medicine had not changed or advanced in the last decade - something I am sure qualified and practicing neonatologists would take issue with. He even corrected defence counsel by saying he was not an ‘expert’, rather he preferred to call himself an ‘independent medical witness’. The majority of his testimony tended more towards the role of being an apologist for the doctors who were present at CoCH at the time, rather than presenting the confident and independent judgement of an expert. His disagreeable and sometimes evasive demeanour during the Lucy Letby trial echoed his previous trial work where the Lord Justice of Appeals rejected his evidence, describing it as “tendentious and partisan expressions of opinion that are outside of Dr Evans’ professional competence” which had “no place in a reputable expert report.” Given that, as defence counsel Ben Myers KC stated during his summation, evidence from the other two medical experts amounts to little more than agreeing with Dr Evans, it is incredible that all of the claims against Lucy Letby rely on the half-baked assertions of Dr Evans regarding air emboli being the only cause that explains what happened to several of these neonates. Assertions that yet again may very well be outside his expertise.

The bulk of Dr Evans’ initial evidence in chief included taking the jury through a collection of medical training videos and explaining key terms and procedures. Among others, this included a training video on the Phillips neonatal patient monitors. During cross examination he undermined his own ‘expert evidence’ first by telling the jury that not everything could be learned from training videos, and then by admitting he had not only never used in clinical practice the Phillips monitors he had been taking them through - but that he had actually never seen one at all.

Dr Evans provided no real suggestion in his testimony for Child A that any alternate potential theories for the cause of death were considered and discounted. In fact, he describes that he came to his conclusion (the air embolus) first, and then found he could even fit the circumstances of Child B to it. This gave the impression that some degree of confirmation bias was inherent in his thinking. The impression of confirmation bias became stronger when Dr Evans rapidly and with little consideration concluded new evidence solely reinforced his theory of the case, such as the claimed skin mottling Registrar Harkness described seeing on Child A for the first time while giving evidence during this very trial. Another example came when, after it had been put to him during cross examination, he unequivocally denied that an infection could even be involved. He brushed infection aside with the bold claim that evidence of infection “would appear on a post-mortem examination”. However, this is not always the case. Unless there was some obvious outward sign of infection, clinical observations at death that strongly suggested it, or the post-mortem request suggested it, the pathologist might not undertake the complete panel of tests that identify a broad range of viral and bacterial infections. Further, the request for Child A’s post-mortem called for an urgent review regarding whether Child A had died due to inheritance of the mother’s blood condition and was therefore looking for clotting rather than infection because, Dr Beech had testified, this finding would significantly affect the ongoing treatment of Child B. The wording and urgency of the request may have directed the pathologist regarding what assessments they performed in order to give a prompt and, potentially life saving, response.

Based on his testimony, Dr Evans’ flawed chain of reasoning for Child A was that:

Because:

1. The baby suddenly crashed; and

2. Resuscitation was unsuccessful;

This means we can conclude:

3. An air embolus was the cause;

Post hoc confirmed by:

4. Air emboli on x-ray; and

5. Registrar Harkness’ refreshed memory of skin discolouration

The links in the prosecution chain required to make out Dr Evans’ diagnosis of deliberate air embolus injection for Child A are therefore that:

Because:

1. Child A was an otherwise stable and healthy neonate; and

We say:

2. A bolus of 3-5ml of air was deliberately introduced intravenously into Child A (a stipulation);

This explains:

3. The sudden unexpected and immediate ‘crash’ of the Child A observed by some or all of:

a. a change of skin colour;

b. apnoea (the absence of breathing); and

c. a reduction or cessation of heartbeat;

d. that occur all of a sudden.

Post hoc confirmed by:

4. The failure of resuscitation (a consequence);

5. The unusual skin discoloration (a sign);

6. The presence of air in the ‘great vessels’ (a sign); and

7. The absence of any other potential cause (a prerequisite).

And means:

8. Whoever injected the bolus of air killed Child A (an assumption);

Given:

9. Lucy Letby was Child A’s designated nurse at the time he ‘crashed’ (a sign);

10. The person most likely to have injected the air is Lucy Letby (an assumption);

Therefore:

11. Lucy Letby is guilty (a conclusion).

This is a case which both prosecution and defence characterise as consisting solely of circumstantial evidence. When considering the strength of circumstantial evidence, the historic but often cited text Starkie on Evidence, 3rd ed., (1842) tells us: “...it is essential that the circumstances should, to a moral certainty, actually exclude every hypothesis but the one proposed to be proved: hence results the rule in criminal cases that the coincidence of circumstances tending to indicate guilt, however strong and numerous they may be, avails nothing unless the corpus delicti, the fact that the crime has actually be committed, be first established...” This is explained by Mr Ian Barker QC as meaning that irrespective of the strength and volume of circumstantial evidence presented, unless every other possible explanation for the outcome has been identified and excluded by inquiry of the most scrupulous attention, it remains nothing more than mere coincidence.

In order, we will now consider the two primary links holding up the prosecution’s chain, without which the rest of the chain must fall:

Link 1: Child A was an otherwise stable and healthy condition

Dr Beech described that Child A, who was born ten weeks premature, had required breathing assistance several times because he repeatedly stopped breathing. Within hours of birth he was given a bolus dose of antibiotics for suspected sepsis - a usually bacterial but sometimes viral blood infection. Unusually, there was no evidence in court to suggest that the bolus dose had been followed up with a protocol for a 5-7 day course of antibiotics as would normally be the case. It is also normal practice for such a premature neonate, especially one who had needed breathing support in theatre and who was being treated for suspected infection, to be immediately transferred to the NICU. Yet, Child A was not transferred to NICU until 2:41am, several hours after his birth. Further, while his first lactate test usually taken from cord blood at birth appeared normal, his lactates at 6:37am were higher than normal - and continued to gradually increase later in the day. Similarly, his observation chart had shown his respiration rate to be gradually increasing over the course of the day. As Dr Evans sought to suggest, each thing in isolation might not mean much, but taken together all of these things suggest a slowly brewing infection. This was compounded by the repeated failure of the trainee doctor to correctly insert the UVC so that the intravenous fluids could be started, the fact that fluids were still several hours in coming even once the UVC had been replaced with the long line, and finally that his fluid input for the day shift was barely 8% of his output (2ml in/25ml out). In totality there is very little to suggest Child A had ever been in a ‘stable’ or ‘healthy condition’.

Link 2: A bolus of 3-5ml of air was deliberately introduced intravenously into Child A

This stipulation arises wholly from the mind of Dr Evans absent any evidence that places a syringe of air anywhere Child A as he lay in the incubator. His claim that a deliberate act with a syringe is the only way air could have become introduced to the ‘great veins’ of Child A also misses another more plausible explanation that arises when we have properly considered the evidence discussed above regarding a possible infection. As we found when investigating common nosocomial pathogens that can also arise in the hospital wastewater that had flooded the neonatal unit (here), several pathogens can cause pneumatosis intestinalis (pockets of air outside the intestinal space), and can lead to an accumulation of air in the large vessels that drain blood away from the gastrointestinal tract and viscera - known as portal vein gas. This is especially true if Child A was gradually developing an infection known as NEC, which is common in neonates, especially those like Child A who are premature and of low birthweight. As we also saw in our earlier article on hospital wastewater pathogens, bacterial infection such as this can also explain Link 5 - the spontaneous purple and red blotches that disappeared within a few hours to a day. Infection, rather than injection with a bolus of air, also conforms to the principles of Occam’s razor - in that nosocomial infections are common and affect a large percentage of hospitalised individuals, can easily become colonised on neonates through contact with colonised surfaces and staff, and explains the fact that none of the four people in the room saw Lucy open the incubator and inject the infant.

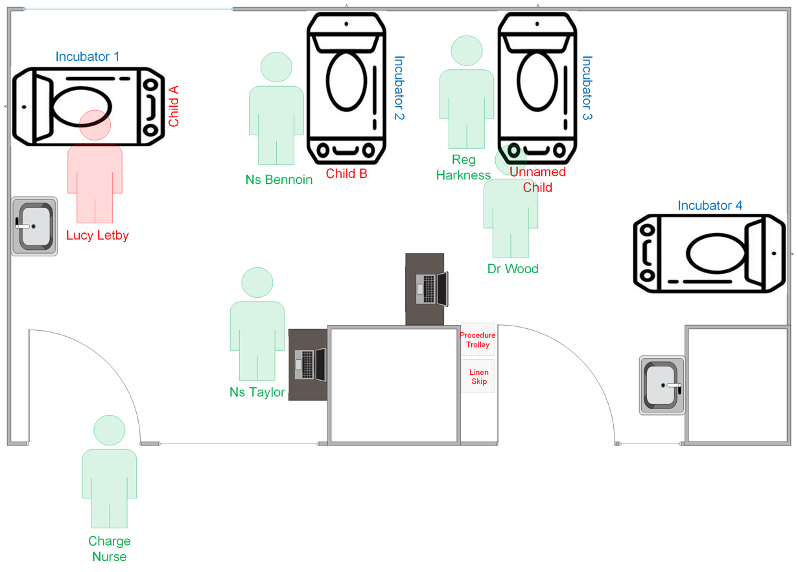

Finally, we turn to Link 10 and the circumstances in Neonatal Unit 1 during the small interval when Lucy Letby is alleged to have performed the stipulated act of drawing up and injecting 3-5mls of air into the UVC. The following diagram shows the approximate disposition of Neonatal Unit 1 at the time. Note that the blue areas around the boundary are windows into the corridors either side of the room. As was seen on the police video, anyone walking in the corridor such as the Charge Nurse had visibility through these windows of events inside the room. Incubator 1 appears to be the most exposed and easiest of the four incubators in the room to observe while, due to the way it was positioned off to the right and partially concealed by what appears to be a pillar or plumbing shaft (the square white area in the bottom right), Incubator 4 was clearly the most obscured. Besides Lucy Letby (in red), there were four other members of clinical staff (in green) in the room at the time.

The medication chart and testimony from Nurse Taylor and Lucy Letby show that the 10% dextrose infusion was recorded as ‘started’ at 8:05pm. It would have taken several minutes to tidy things away and for whichever nurse was in the sterile gown and gloves to disrobe and for both to perform post-procedure hand-washing and then document the procedure. At this point, Lucy returned to observing Child A while Nurse Taylor went to the computer to start her 8:18pm clinical note. Nurse Taylor returned to Incubator 1 to assist Lucy Letby only minutes later. At 8:26pm when Lucy requested assistance from the doctors in the room, the Charge Nurse observes events through the window in the corridor and also comes to assist.

The totality of evidence as testified by Lucy Letby and the other clinical staff present, when contrasted to the simple truth of the room where events are said to have occurred, leads the conclusion that the opportunity for Lucy Letby to have clandestinely: (i) unwrapped a 5ml syringe from it’s crinkly plastic sterile wrapping; (ii) draw up 5ml of air; (iii) open the incubator without being seen; (iv) injected the air into the UVC that was being used to infuse the dextrose solution without being observed and without triggering the alarm on the infusion pump; (v) closed the incubator; and (vi) disposed of the syringe - all in a few short minutes and without being noticed by the four other people in the room, simply was not there.

The next post in this series can be found (here)

*** *** ***

The Law Health and Tech Newsletter is a 100% subscriber funded publication. This work is not funded by an employer, commercial or charitable organisation. Please consider a paid subscription the help me to continue this work.

*** *** ***

Great article again. Two things that could have increased the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in that unit in a specified time period that have more to do with bad management than a bad nurse:

(1) poor breast feeding rates in the neonatal unit. This is a major risk factor for NEC in the NICU. Is the Countess of Chester recognised as a "baby friendly" unit?

(2) overuse of co-amoxiclav in antenatal women at risk of preterm labour. This is a known risk factor for NEC and neonatal death (HR of 14x for mortality from NEC). Known = known in the literature which doesn't stop bad obstetricians giving it out.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22933088/

I would look at those two factors around that time at that hospital if I were on the defence team.

UPDATE: CoC claims to be "baby friendly" accredited. It would be worth trying to get hold of one of these team members to see if the neonatal unit was an active participant, or they were still running old-school formula based doctrines. https://www.coch.nhs.uk/all-services/infant-feeding

"During cross examination he undermined his own ‘expert evidence’ first by telling the jury that not everything could be learned from training videos, and then by admitting he had not only never used in clinical practice the Phillips monitors he had been taking them through - but that he had actually never seen one at all." It's as if the prosecution did not really want an expert witness. This is farce, though tragic.