LL Part 14: Insulin - the first issue

BBC, Frank Haviland and others say it wasn't prescribed to anyone on the unit

Continuing on from our previous post here.

Several commentators, but most prominently the BBC’s Tom Mullen and Daily Sceptic’s Frank Haviland, have claimed that no child was being administered insulin on the Countess of Chester Hospital (CoCH) at the time Baby F was allegedly murdered harmed by Lucy Letby with insulin.

Is it pedantry, or an attempt to distract and mislead the public?

What do we know (so far)?

On the basis of existing academic and medical literature contrasted to the testimony and evidence discussed in the previous 13 articles in my Lucy Letby case analysis:

Premature and small-for-gestational-age (SGA) neonates have an almost 335% increased risk for conditions of altered glucose management that can persist even while they are receiving insulin infusions (here and here). Hyperglycaemia in the neonate is therefore common (here and here). Hyperglycaemia can also be a sign of an otherwise asymptomatic bacterial or fungal infection, sepsis, septic shock, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and acute intracerebral bleeding in neonates (here and here). The observation of hyperglycaemia in the first day of life is linked to a significantly increased mortality (here), and hyperglycaemia and insulin therapy each pose significant risks for the neonate (here and here).

Baby E was born on July 29th, 2015. Baby E was premature and only weighted 1.3kg when born. He died of what was initially ruled Necrotising Enterocolitis (NEC) during the early hours of August 4, 2015. As we saw in LL Part 13, Baby E had been hyperglycaemic (had high blood sugar levels) during the entirety of his five days on the CoCH Neonatal Unit, and had received varying doses of insulin as a continuous infusion every day during his short life.

Baby F was also born on July 29th, 2015. He occupied the cot directly next to Baby E and, by virtue of being his identical twin, had the same surname. When a baby is born the common way of addressing that baby on forms and systems is “Baby [Mum’s Surname]”. In my discussions today with several midwives at a unit that receive babies from CoCH, it became apparent that there may not be a standard protocol for the labelling of twins. Some midwives label them as “Twin 1 [Mum’s surname]”, while others label them as “Baby [Mum’s Surname] Twin 1” or “Baby 1 [Mum’s Surname]”. The labelling of twins can also change antenatally to postnatally as antenatally the lower twin is always “Twin 1” while postnatally the twin delivered first is “Twin 1”. In a caesarean birth the upper twin is often delivered first. This can lead to confusion if Twin 1 antenatally was found on ultrasound to have an abnormality and after a caesarean birth is documented as Twin 2 postnatally. I was told about incidents where the wrong twin has received treatment either due to the antenatal/postnatal confusion, or simply because harried paediatricians, midwives or neonatal nurses have thought they were supposed to be administering medication to “Baby 1 Smith” but for a variety of reasons (distraction, dyslexia or dyscalculia…) ended up unintentionally administering the drug to “Baby 2 Smith” - or vice versa.

It is not uncommon to observe the hyperglycaemic issue in one twin, also occuring in the other (here and here). For example, studies show that where one of a set of twins has Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), around 50% of their sibling twins will also have or develop the condition. This rises for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), wherein 3-in-4 (75%) of twin siblings will also have or develop the condition (here). The risk of any child being diagnosed with a condition of altered glycaemic control also increases if either or both of the parents are themselves diabetic.

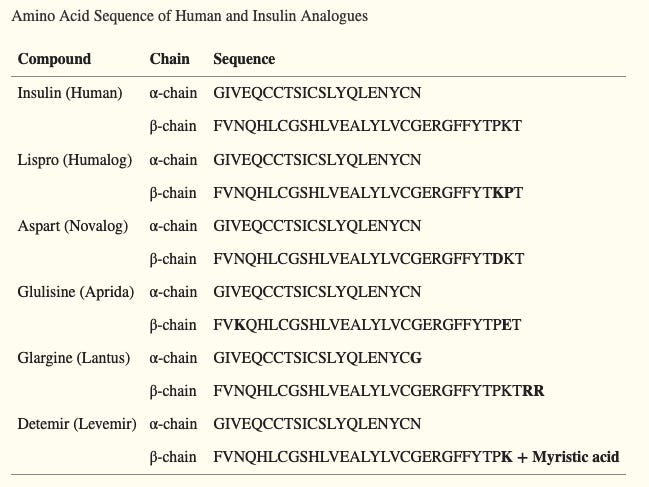

Insulin consists of two amino acid chains - a 21-amino acid alpha chain, and a 30-amino acid beta chain (here). These chains are held together by two interchain disulphide bonds. The alpha chain also has an additional single inter-chain disulphide bond (between amino acids 6 and 11).

Synthetic insulin manufacturers attenuate a slight variation into the beta chain which enables identification of their specific product (here). There are a variety of approaches available using LC-MS/MS that can be used to categorically identify whether the insulin is of human (endogenous) or synthetic (exogenous) source and, if synthetic, the specific manufacturer of that product.

Initial Conclusions

Given that Baby E and Baby F entered the neonatal unit at the same time and were treated in the same room of the unit in side-by-side incubators, it is either: (a) an outright lie; (b) deliberately misleading; or (c) absolute pedantry to claim that no babies were being prescribed insulin on the unit at the time Letby was accused of poisoning Baby F’s TPN with insulin. An outright lie if we consider that Babies E and F were side by side for 5+ days while Baby E was prescribed and being administered insulin; and deliberately misleading or outright pedantry if what Tom Mullen and Frank Haviland are alluding to is nothing more than ‘the handful of hours between when Baby E died and Baby F was retrospectively seen to have had a reaction to what is presumed to be insulin.’

The use of simultaneous insulin and c-peptide as a measure of a suspect’s guilt when deciding whether a victim has been administered an inappropriately high dose of insulin has been called into question by many, including Professor Vincent Marks (here, here and here). Other prosecutions of insulin poisonings or murders have been overturned (here and here), and in 2021 the somewhat famous Colin Norris case in the UK has finally been referred by the CCRC back to the UK Court of Appeal (here) because the experts agreed that the hypoglycaemia in the four elderly patients could actually be explained by natural causes and not the possibly non-existent alleged insulin injections Norris had been accused and found guilty of administering to them.

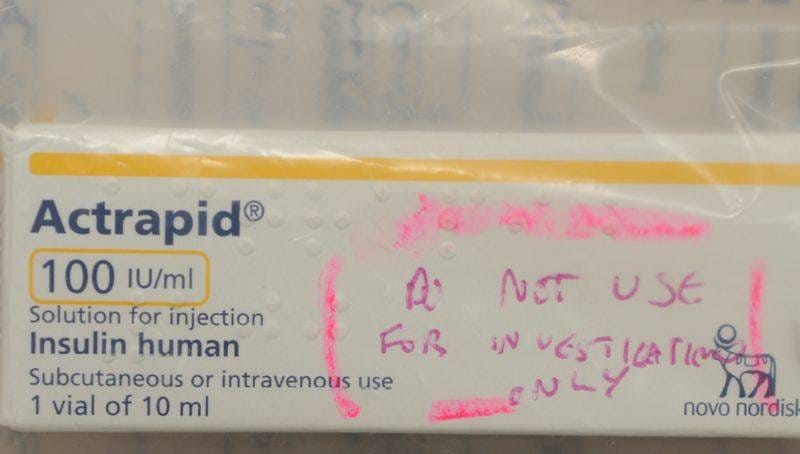

There is also the matter of the test used to identify that the insulin was ‘synthetic’. Many online pundits have pointed to the fact that the protocol for the test explicitly says it should not have been used for this purpose. Leaving that aside, one has to wonder why one of the LC-MS/MS tests I mention above was not used, as this would have not only identified if the beta chain was synthetic, but also the manufacturer of that synthetic insulin. It seems to me that claiming on the basis of a single (possibly inappropriate) test that the insulin is synthetic and then showing the jury an image of a pharmaceutical carton of the type used on the CoCH neonatal unit that says Actrapid insulin and saying “this was what it was” is indefensible conjecture and taints the jury.

If I had been a member of the jury the prosecution would have had to prove to me that:

The insulin was indeed synthetic through the use of an appropriate test that does not have a protocol precluding its use for this purpose, performed at an appropriate laboratory by a suitably qualified laboratory technician.

The insulin beta chain is the same as the beta chain for the Actrapid brand of insulin that was the only brand used on the CoCH neonatal unit.

The insulin could not have been administered accidentally - such as a nurse mis-reading an order for “Baby 1 Smith” (Baby E) and unintentionally administering it to “Baby 2 Smith” (Baby F).

And finally;

That in the presence of positive findings for all of the above (1-3), Lucy Letby could be identified as the only plausible remaining explanation.

I will return to the issue of insulin after we have explored the demise of Baby F

The next post in my series on the Lucy Letby trial can be found here.

inference is far, very far, from beyond a reasonable doubt....

“One question in need of further attention is when guilt is proven beyond a reasonable doubt (BARD) in criminal trials. This article defends an inference to the best explanation (IBE)-based approach on which guilt is only established BARD if (1) the best guilt explanation in a case is substantially more plausible than any innocence explanation, and (2) “there is no good reason to presume that we have overlooked evidence or alternative explanations that could realistically have exonerated the defendant”

There is every good reason to question the evidence not led by the defence!

This is the most serious type of criminal case, for murder. How did the defence not raise these issues? What happened to the 'beyond reasonable doubt'? We are spoilt for choice of reasonable doubts.