How unusual was the spike in neonatal deaths when Lucy Letby was working?

Our analysis, that even the preprint servers don't want you to see

Before I launch into the neonatal death analysis, those readers that follow us on Twitter/X may have seen our recent tweets on academic censorship. We tried to publish this analysis as an academic preprint on arXiv and medRxiv this week, only for both preprint servers to reject our work and refuse to release it. More on that at the end of this post.

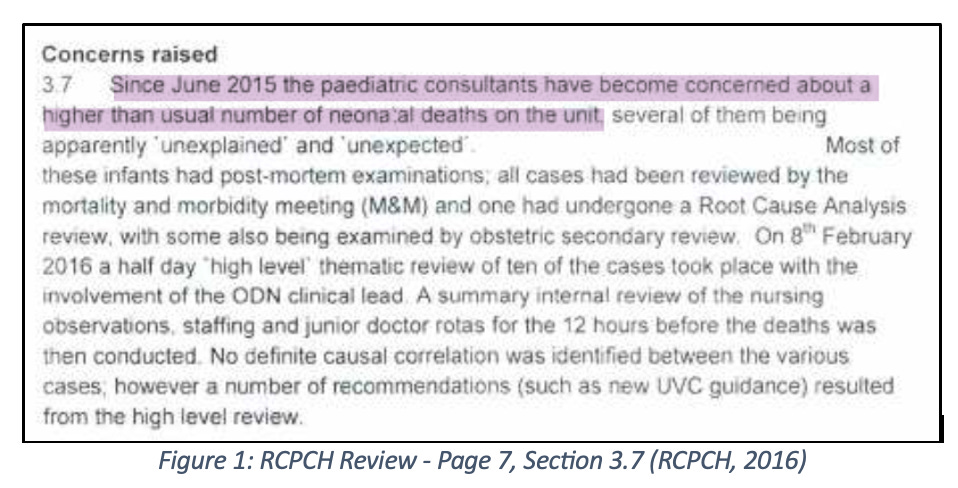

Even before the first trial started in mid-October 2022, Lucy Letby and the Countess of Chester Hospital (CoCH) had dominated the mainstream news and become household names, at least in the United Kingdom. The Royal College of Paediatric and Child Health (RCPCH) invited review report (RCPCH, 2016) and media articles both before and throughout the trial repeatedly claimed that during the key years of 2015 and 2016, the years when Letby is said to have killed seven babies and attempted to murder seven others, there was a sudden spike in neonatal deaths at Countess of Chester Hospital (CoCH). However, what has always been absent, in the report, court testimony and in newspaper articles, is evidence supporting this claim. Using data available to police, barristers, the court and journalists at the time, we show that, from a strict probabilistic view, there was nothing unusual about the number of neonatal deaths CoCH disclosed in their FOI (CoCH, 2018).

The Data

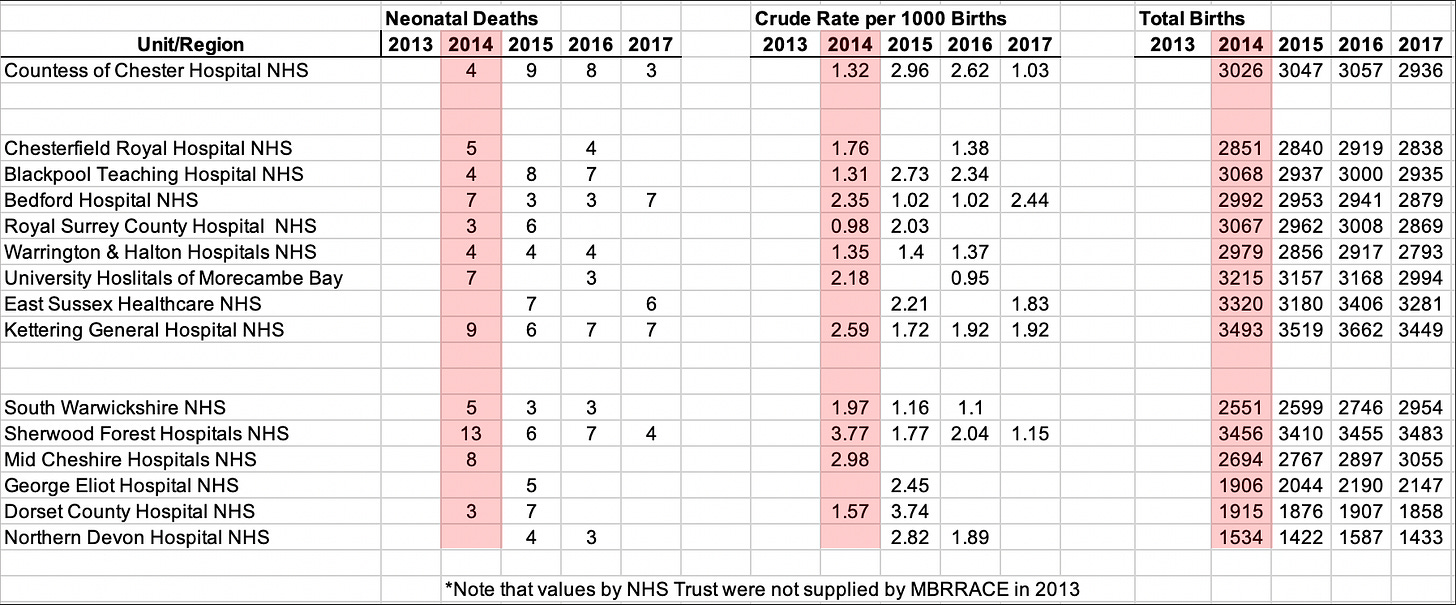

We developed a dataset of births, stillbirths and neonatal deaths for the whole of England from data published by the ONS and MBRRACE for a five year period that included 2015 (MBRRACE, 2015; ONS, 2015) and 2016 (MBRRACE, 2016; ONS, 2016). From that larger dataset we extracted a comparator dataset of fourteen hospitals, shown in Table 1.

For reasons that will become clear, the most relevant data for identifying whether there is a spike is this comparator dataset. Cursory analysis of the table alone shows there isn’t anything to immediately suggest the presence of a true spike in neonatal deaths. While many hospitals appear in one year or another to have done better than CoCH, some hospitals performed similarly - for example, North Devon and Blackpool in 2015, or significantly worse - for example, Dorset County in 2015, Sherwood Forest in 2014 and Bedford in 2017. See below for our thorough analysis of CoCH’s performance against these comparator hospitals.

The larger country-wide dataset was used to derive an accurate national average for neonatal deaths in England. While it does not affect that overall national average, the available data were apportioned by Local Authority area of the mother’s residence rather than by hospital. However, MBRRACE data also provided the number of births for many NHS trusts during 2014-2017 to allow us to identify and model births at CoCH independent of all other births recorded to mothers within the hospital’s catchment area, Cheshire West and Chester. On average, while 5,200 (5,174 - 5,326) mothers in Cheshire West and Chester gave birth annually, only 3000 (2,936 - 3,057) births occurred at CoCH. The resulting larger dataset allowed us to determine the average neonatal deaths per 1000 births in England for each year [total neonatal deaths/(total births/1000)].

There are several different ways a woman may give birth that explain the difference between the number of births within a given NHS Trust, and the sometimes much larger number of births recorded for mothers in the Local Authority area surrounding that Trust:

If the woman is found to be a low risk pregnancy that will not require any medical assistance beyond the presence of two midwives, she may choose or be offered the option to have a home birth. A range of Local Authority, NHS and private midwifery service providers are available for home births. Around 2.3% of births in any year are home births, which for the Cheshire West and Chester area amounts to approximately 123 births annually.

A further 12% or 639 births in the Cheshire West and Chester Local Authority region each year occur in what are sometimes termed birthing units but are known within the NHS as Midwifery Led Units (MLU). The Blossom Birthing Unit at CoCH is the MLU in Cheshire West and Chester staffed by midwives alone and, as with home births, only take the lowest risk pregnancies who are all expected to have normal vaginal deliveries needing minimal assistance and support.

The remaining 85.7% of births occur in the obstetric unit (OU) of the local hospital if the mother and baby fall within the acuity level of the services available at that hospital.

Many with more serious medical conditions each year are referred out to another nearby hospital that is able to cater for their specific needs, which in the case of CoCH could mean a mother is giving birth at Liverpool Women’s Hospital, Arrowe Park Hospital, or at another facility further away. From at least 2012 up until June 2016 CoCH was a Level 2 LNU facility. So if, for example, there was only one neonatal bed available and the choice was between delivering a mother at or near term with no complications, or a mother who was going into labour 8-10 weeks premature, CoCH would have diverted the near-term uncomplicated mother to a Level 1 SCBU hospital in favour of providing their available Level 2 LNU cot to the premature neonate that was going to need it. Both actions - diverting more serious cases to a Level 3 NICU and less serious cases to a Level 1 SCBU, were standard operating practice for a Level 2 LNU unit and were intended to ensure each facility catered to patients whose needs matched the service and acuity level each facility provided.

It is also common for a mother living near the border of her home local authority to be closer to and end up giving birth at the maternity unit of the hospital in the neighbouring local authority area.

For all these reasons, the number of births in the Local Authority area will always be larger than the number of births recorded at the hospital within that area.

Neonatal deaths per 1000 births for the whole of England, Cheshire West and Chester, and CoCH are provided in Table 2. The first thing we observe is that neonatal deaths per 1000 births for mothers in Cheshire West and Chester were below the national average in all years except 2014. However, on the raw data alone, they appear above average for CoCH in 2015 and 2016. It is possible that this crude representation absent further information such as the actual number of births in each year and comparison to other similar hospitals was the catalyst for the spike claims.

The Comparator Hospitals

This section describes the comparator hospitals by neonatal unit type, and compares and contrasts them in each year with CoCH.

In Table 1, the first cluster of eight hospitals are those that were observed to deliver a similar number of babies as CoCH each year - the ‘similarly sized’ neonatal units. On request, the second cluster of six hospitals were identified by a Senior NHS Midwife and Clinical Midwifery Educator as those sharing a similar demographic, deprivation or some other variable with CoCH - the ‘midwife selected‘ neonatal units. Empty cells for both groups of hospitals are those where values were not provided in the publicly available data.

Level 1 SCBU:

Bedford, Royal Surrey, University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay, East Sussex Healthcare, Kettering General, South Warwickshire (Warwick Hospital), Sherwood Forest, George Eliot, Dorset County and Northern Devon are all Level 1 Special Care Baby Units (SCBU).

SCBU take the lowest acuity, lowest risk, nearest to full term neonates born after 32 weeks gestation. SCBU monitor these babies, perhaps providing supplemental oxygen, tube feeding, treating low blood sugars and providing phototherapy - where babies with jaundice, which is a common condition observed in the first days after birth, are put under UV lights to help their bodies stabilise their bilirubin levels.

Level 2 LNU:

Chesterfield, Warrington & Halton, and Mid Cheshire are all Level 2 Local Neonatal Units (LNU). CoCH was also a Level 2 LNU up until mid-2016.

LNU currently take neonates born after 27 weeks and weighing over 1000 grams. These babies have higher acuity, and higher risk, and require more care and closer attention. An LNU can provide short term intensive care, usually for up to 48 hours before the possible need for transfer to a NICU may be necessary, they also care for babies observed to have periods of apnoea (loss of breathing), babies that need non-invasive assisted breathing, tube and parenteral (veinous) feeding, and can provide initial assistance for babies to stabilise them prior to transfer to a NICU.

Up until June 2016 CoCH was an LNU and were allowed to take babies weighing over 800 grams - babies as small as Baby C. Many neonates at CoCH were being repeatedly intubated and extubated. LNU are now restricted to non-invasive assisted breathing such as CPAP and nasal cannula and should only be intubating babies that are being prepared for transport to a Level 3 NICU. The weight and assistive breathing limitations appear to have been changed since the events of CoCH, and this is probably for the better as it ensures that babies under 1000 grams or requiring intubation and ventilation that require more intensive care are transferred to a NICU.

Level 3 NICU:

Blackpool is the only Level 3 Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) included in the table.

NICU provide care for the highest acuity, highest risk, least likely to survive neonates born before 27 weeks gestation. These are babies that often require invasive intubation and ventilation, and support not just for breathing but also to maintain cardiac and blood pressure function and feeding. The NICU also takes babies of low birthweight (under 1000 grams), babies that require cooling therapy to reduce brain injury, and babies that require specialist surgical intervention.

2014

From Table 1 we see that in 2014 the Level 1 SCBU unit at Sherwood Forest had more than three times as many deaths as CoCH, and Kettering’s Level 1 SCBU had more than double. The similarly sized Level 2 LNUs at Chesterfield and Warrington & Halton had similar numbers of neonatal deaths as CoCH, while Mid Cheshire’s Level 2 LNU had exactly twice as many as CoCH. Finally, the Level 3 NICU at Blackpool that cared for around 3000 babies, including those with the highest care needs and highest risk, had the same number of deaths as CoCH. What we observe is that CoCH were doing better than some Level 1 SCBU units and were on par with their Level 2 LNU peers. However, we must remember that 2014 was the only statistical anomaly for CoCH - it was the year that neonatal deaths at CoCH were significantly below both the national and their own average.

2015-2016

In 2015 and 2016 the number of deaths observed at CoCH were at the upper limit level that was observed both before the anomalous year in 2014, and after Letby was dismissed and the police investigation started in 2017. While in Table 1 CoCH also has the highest number of neonatal deaths for both years, this is only comparatively higher by a single death in each year than both the similarly sized and midwife selected hospitals.

In both years the higher risk Level 3 NICU at Blackpool had one fewer death than CoCH, but also had fewer births in both years than their 2014 total, and 110 (3.6%) fewer births in 2015 and 57 (1.8%) fewer births in 2016 than CoCH. Further, we observe that the deaths per 1000 babies margin between CoCH and Blackpool remained comparable from 2015 to 2016 - showing that even as the number of births changed from one year to the next, the number of deaths at each unit per 1000 births as compared and contrasted between the two geographically disparate units has an almost equal rate of relative change. Finally, while the lower acuity Level 1 SCBU at Dorset County had two fewer neonatal deaths than CoCH in 2015, their neonatal death rate per 1000 births was observed to be 26% higher than CoCH (3.74 vs 2.96).

2017

For 2017 we can see that CoCH actually had a lower number of neonatal deaths and rate per 1000 births than any of the four comparator hospitals for which MBRRACE provided crude values. This change is possibly due to three factors:

CoCH’s reclassification from a Level 2 LNU to a Level 1 SCBU at the end of June 2016.

Increased attention on CoCH’s neonatal unit from both within and without the hospital that may have led staff to be more focused on their work, more likely to refer babies on the cusp of gestation and weight limits to another hospital, and increased clinical supervision from senior medical staff.

Initiation of the police investigation.

CoCH Bayesian Analysis

Using the data from the 14 other relevant hospitals, we can answer formally the question: were the number of observed deaths at CoCH really unusually high? Specifically, for each year we can determine the formal probability of observing at least the number of neonatal deaths at CoCH by chance alone.

We have a total of 35 data points (11 in 2014, 11 in 2015, 9 in 2016, 4 in 2017). From these we learn a (beta) distribution (see the Appendix in the full preprint version linked below for details) for the rate of neonatal deaths per 1000 births. This distribution has:

Median 2.078

95% confidence interval (0.32 – 6.57)

So how unusual were the 9 neonatal deaths from 3047 births at CoCh in 2015?

Based on the above learnt ‘population’ distribution for rate of neonatal deaths, the expected number of neonatal deaths is:

Median 6 (mean 7.47)

95% confidence interval (0.6 – 22.4)

As shown in Figure 1 of the Appendix in the preprint version linked below, this enables us to deduce that the probability of observing at least 9 neonatal deaths by chance alone is 34.2%

So how unusual were the 8 neonatal deaths from 3057 births at CoCh in 2016?

Based on the above learnt ‘population’ distribution for rate of neonatal deaths, the expected number of neonatal deaths is:

Median 6 (mean 7.4)

95% confidence interval (0.61 – 22.4)

As shown in Figure 2 of the Appendix to the preprint version linked below, this enables us to deduce that the probability of observing at least 8 neonatal deaths by chance alone is 40.4%

How unusual would it be to observe at least 9 followed by at 8 deaths in consecutive years by chance alone at the CoCH?

Assuming independence between years we can simply multiply the probabilities learnt in the above two cases. So, the probability of observing at least 9 and 8 neonatal deaths in two specific consecutive years at the same hospital purely by chance is 13.8%

Conclusion

We have shown that there are 14 other hospitals in the UK which, in terms of number of births and relevant neonatal care profile, can be reasonably compared to CoCH. Using the available neonatal deaths data from these hospitals for the years 2014-2017 (excluding CoCH), we have applied standard Bayesian techniques to learn the overall population distribution of neonatal deaths rates for hospitals similar to CoCH. Based on this learnt distribution, for each of the years (2015, 2016) where there was a claimed ‘spike’ in neonatal deaths, we found that the probability of observing at least the number of deaths that were observed at CoCH by chance alone was not small (34.2% probability for the 9 deaths in 2015, and 40.4% probability for the 8 deaths in 2016).

There was, thus, nothing especially unusual about the ‘spike’ in deaths at CoCH in 2015 and 2016.

A preprint version of this analysis is available from the following ResearchGate link:

http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13777.54886

The preprint version includes a reference list and presents the Bayesian binomial model showing how the results above were computed.

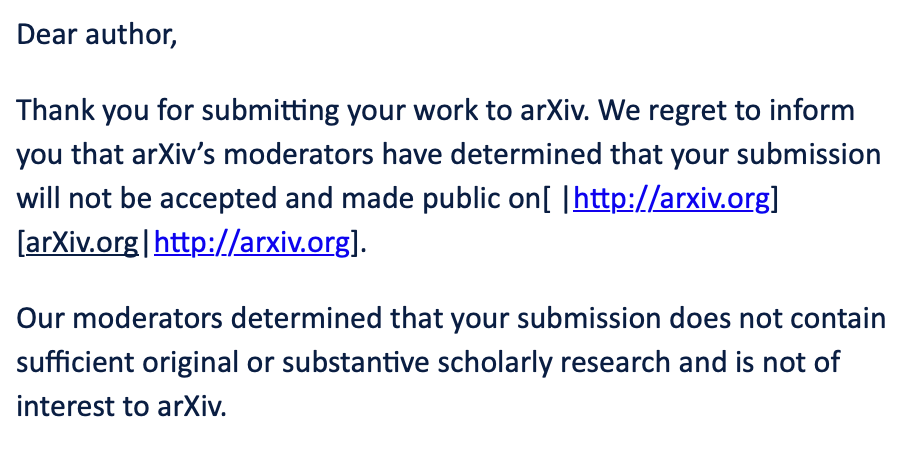

Academic Censorship

We had thought the Covid period of academic censorship that has sought to silence and cancel academics like us since mid-to-late 2020 was over (see here, here, here and here). How wrong we were. As we all try to keep up with the revelations of the Thirlwall Inquiry, we attempted to publish this analysis as a preprint, first on arXiv. The response from arXiv was that our entirely novel and original work does not contain sufficient original or substantive scholarly research and was not of interest to arXiv. Frankly, they simply did not want to be involved in disseminating work that is counter to the ‘baby killer’ narrative and clearly don’t want you to see it.

After that we submitted the manuscript to medRxiv. In a little over 24 hours we received a similar response, however this time we were told that our work was not clinical and did not contain new data. Again, it is clear they simply did not want to be involved in disseminating work that is counter to the current mainstream ‘baby killer’ narrative and clearly don’t want you to see it.

Academic censorship of anyone, and their work, that might tend to show that the mainstream narratives on anything from covid, net zero or even Lucy Letby is alive and well…

And continues.

Erratum: The year in the first paragraph previously said 2023 - this has been corrected to 2022.

I was upset to read on the BBC that "A solicitor representing the families of six victims of Lucy Letby said online speculation about the safety of the nurse's conviction was "upsetting" for all of her clients". I remember being impressed by Dr Jim Swire, the father of one of the dead in the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing arguing that he did not accept the guilt of al-Megrahi - he wanted the truth, not a scapegoat. Sadly, the rejection by arXiv and medRxiv tells me there is something to hide, there are powerful interests that do not want the truth. You are presenting a novel analysis of clinical relevance.

A few weeks ago I came across BlackBeltBarrister on YouTube who recently has made some comments on oddities in the Letby trial. Worth a view.

Personally, on that other front I can’t believe that I have been send an email about having that latest covid booster, which I have declined for three years. The system is trying to kill me off.

Great work. It is so wrong that there has been no publication in the preprint servers.